A Larger-than-Life Project

Researchers Receive Grant to Digitally Collect 50 of the World’s Largest Animals and Scan an Entire Blue Whale Skeleton

Idaho State University’s Idaho Virtualization Laboratory in the Idaho Museum of Natural History has been tasked to digitally collect the skeletons of 50 of the largest animals in the world, from marine mammals to giraffes, about anything bigger than a cow.

Technicians from the museum’s Idaho Virtualization Laboratory, which received a $175,000 grant from the National Science Foundation in August, will travel to the University of California, Berkeley, California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco and the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology in Boston over two years to make 3D scans of hippos, elephants, rhinos, marine mammals, fish and other large animals.

The Idaho Virtualization Laboratory also received a $20,000 grant in January from the Noyo Marine Science Center in Briggs, California, to scan the entire skeleton of a blue whale that washed ashore in California.

“The bigger part of the project that we are part of is this nationwide effort by the National Science Foundation to scan all of the vertebrate animals,” said Leif Tapanila, director of the Idaho Museum of Natural History. “This is a monstrous task. Ultimately, they want to have a digital version of every animal on the planet. Let’s just deal with the vertebrate animals like mammals, reptiles and fish — there are thousands of species right there.”

Until recently, only smaller animals were able to be scanned with the tools that were available, CT and MRI scanners. Whole animals were put through the scanners, but there was a limitation on the size.

“All the large animals that you know of that are in a zoo, you can’t pack many of those into a scanner, let alone there aren’t any of those in collections,” Tapanila said. “If we have big animals we have their bones. So that is where we come in. We’ve been scanning bones for a long time and we have the technology and we know how to do it, so the NSF funded us to scan the 50 largest terrestrial animals.”

The Idaho Museum of Natural History’s efforts will be led by Jesse Pruitt, Idaho Virtualization Laboratory manager and technology specialist, who will oversee teams of ISU students who will use laser scanners to make 3D digital models of all the bones of 50 different large animals. The ISU students working on this project in the field and in the Idaho Virtualization Laboratory include graduate students and undergraduate Career Path Interns.

Leif Tapanila, left, and Jesse Pruitt

he Idaho Museum of Natural History’s efforts will be led by Jesse Pruitt, Idaho Virtualization Laboratory manager and technology specialist, who will oversee teams of ISU students who will use laser scanners to make 3D digital models of all the bones of 50 different large animals. The ISU students working on this project in the field and in the Idaho Virtualization Laboratory include graduate students and undergraduate Career Path Interns.

“This fits in overall with what we’ve done before and it is a continuation of that niche that we are filling right now in the nation as being able to scan at this level of quality and to deal with this kind of a task. No one else in the country, outside of the Smithsonian, could do this kind of work at this scale,” Tapanila said.

Scanning every bone of each of these species will be a painstaking process.

“Quite literally, working with curators and collection managers at the museums, we have to haul out every bone from cabinets, put it on a table, scan the surface, and rotate it and scan every other surface, and then put it all together,” Tapanila said. “We do this for every bone.”

Once the bones are scanned, their digital representations will be posted to a public website where they can be viewed.

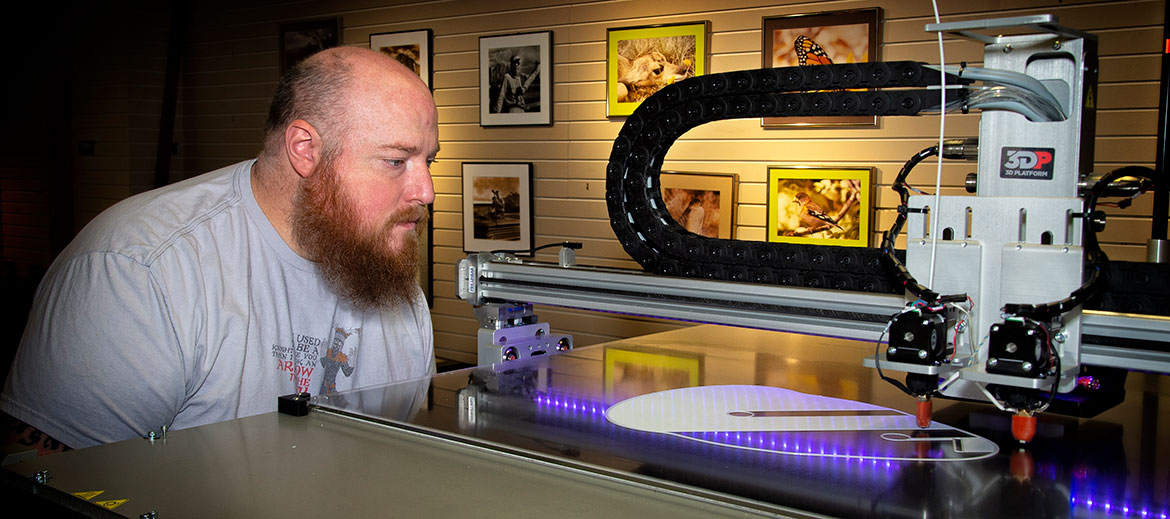

Jesse Pruitt working with a scanner

“The major reason the NSF feels it is important to create this database of life is for researchers as end users,” Tapanila said, “but I am more excited about what we’ll be able to do with all these digital products on the educational sides and with exhibits. I can imagine a future where we are making whole new exhibits off this fundamental data.”

He presented an example of how the digital bones could be used. An entity, like the Idaho Museum of Natural History could use 3D printers to print of bones from a variety of animals so people could compare them.

“Imagine, you’ll have the flipper of a whale and wing of a bat and have the hand of a frog,” Tapanila said. “You could maybe blow up the wing of the bat and shrink the size of the whale flipper, so now you can see that wrist bone in the whale is the same as that wrist bone of the bat, so you can see that it is the same equipment that underlines what a mammal is – we are just adapted different for the different functions that we need for environments. That is pretty cool. We are kind of getting to the building blocks and connectedness of life.”

Tapanila described ISU’s big-animal scanning project as a module in the National Science Foundation’s umbrella program, Open Vertebrate (oVert) Thematic Collections Network (TCN) that has a goal of scanning more than 20,000 smaller vertebrate specimens. ISU received the grant from the NSF Partner to Existing Networks program.

The co-principal investigator in this project is David Blackburn, of the University of Florida and Florida Museum of Natural History, who is leading the NSF’s oVert efforts.