The Bear Lake Valley

The Oregon Trail in Bear Lake Valley

The Oregon Trail entered Bear Lake Valley near present Montpelier and followed the valley of the meandering Bear River. Travelers remarked on the abundant flowers, berry bushes and mosquitoes on this stretch of trail, in distinct contrast to the dry and windy sagebrush plains of Wyoming.

Osborne Russell comes to Bear Lake Valley

On the 2nd of July, 1834, Osborne Russell, traveling with Nathaniel Wyeth's band of trappers left Ham's Fork, Wyoming, crossed a high range of hills (the Preuss Range), and

"fell on to a stream called Bear River which emptied into the Big Salt Lake. This is a beautiful country. The river which is about 20 yards wide runs through large fertile bottoms bordered by rolling ridges which gradually ascend on each side to the high ranges of dark and lofty mountains upon whose tops the snow remains nearly the year round. We traveled down this river northwest about 15 miles and encamped opposite a lake of fresh water about 60 miles in circumference which outlets into the river on the west side." Haines (1965, p. 3).

Bear Lake and Bear River

The Bear River was named in 1818 by Donald Mackenzie and a party of trappers. Bear Lake is shallow, about 20 feet deep at most, but it overlies up to ten thousand feet of lake and marsh deposits. The lake at the south end is fed by streams from the nearby mountains, and not by the Bear River, which flows north of Bear Lake, and into which the Lake formerly drained. Today water is pumped out of the lake through a series of canals controlled by Utah Power and Light Company and several irrigation companies.

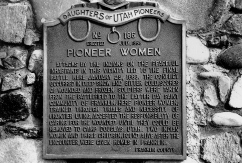

Early Settlement of Paris

Charles C. Rich and a group of Mormon settlers founded Paris on Sept. 26, 1863. A young man named Frederick Perris surveyed the town and left for California. The town was named after him, and the incorrect spelling was used. Robert Price, one of the leaders in Paris after 1870, built a sawmill at the mouth of Paris Canyon, designed to provide building material for all the settlements in the Bear Lake region.

Utah or Idaho?

Unfortunately for the early Mormon settlers, the newly formed communities of Paris, Saint Charles and the country around the north end of Bear Lake were not in Utah, but in Idaho. Nonetheless, the 1,925 residents of Bear Lake County were included with the Utah Territorial census of 1870. The location of the boundary was in dispute until it was surveyed in 1872. Bear Lake County was established in 1875 with Paris as county seat, broken out of what had been Oneida County. For several years in the 1880s, C.C. Rich served in the Utah legislature and his son in the Idaho legislature, though they both lived in Paris.

Montpelier

Montpelier (elevation 5,920) was founded in 1864 as a Mormon farming community, comfortable with its remoteness. The west-building Oregon Short Line reached the community in 1882, and for a while there were two Montpeliers, one the established Mormon community, the other the largely Gentile railroad outsiders, regarding each other with suspicion. The railroad built a repair shop and a roundhouse and the town served until recently as a railroad division point. Farnworth (1993) relates stories of Montpelier and the Oregon Short Line. At the time of statehood in 1890 Montpelier was the 9th largest city in Idaho.

The population of railroad workers was separate from the Mormon settlers of Bear Lake County, who farmed the western and southern ends of the lake and established the county seat at Paris. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the road from Paris to Montpelier was often impassable due to washouts and mud. In 1911, the railroad company built a branch line to Paris to serve the farming area but motor vehicles and World War II brought its demise in 1943. World War II also brought a large airfield out on the flat marshy country north of Bear Lake, but it is almost totally unused now.

Geology

Bear Lake Valley is topographically high, (near 6,000 feet) and has long cold winters and short summers. The valley is a fault-bounded basin, or graben, with normal faults on both the east and west sides. The largest fault borders the east side of Bear Lake, and has been dropping the valley downward and tilting it eastward with respect to the Bear Lake plateau for perhaps 10 million years. Total displacement on this fault is close to 10,000 feet.

The mountains of the Preuss and Aspen Ranges to the northeast of the Bear Lake Valley belong to the Meade thrust plate of the Idaho-Wyoming thrust belt. This is the area that contains the rich phosphate deposits of the Permian Phosphoria Formation, deposited in a nutrient-rich warm sea about 250 million years ago. Mining of the Phosphoria Formation has been and will be a major influence on the economy of not only the Bear Lake area, but much of southeast Idaho.

The Bear River Range on the west of the Bear Lake Valley contains Lower Paleozoic and Late Proterozoic rocks of the Paris thrust plate. The Paris thrust extends along the east side of the Bear River Range and places these older rocks over younger Paleozoic rocks of the Meade thrust plate.

Phosphate Mining History

Underground phosphate mining began in Georgetown Canyon in the early 1900s and a phosphate processing plant was built in 1957. Open pit mining began in 1958. An avalanche destroyed many of the facilities and the processing operations were moved to Conda, north of Soda Springs, in 1964.

The oldest phosphate mine in Idaho is the Waterloo Mine in Montpelier Canyon, about 3 miles east of the city of Montpelier. Mining began in 1907 and the mine was closed in 1929. The property was reopened from 1945 to 1958.

Underground mining of phosphate began in the Slight Canyon area north of Paris in 1920.

Soda Springs Area

Oregon Trail

Soda Springs was a well-known landmark on the Oregon Trail which passed along the Bear River and turned northwest at Soda Point (Sheep Rock). Ruts can be seen in many places along the Bear River, including on the north side of Soda Point Reservoir in the Soda Springs golf course and in the Historic Park area just west of town. The mineral springs were remarkable to the early Pioneers. Steamboat Springs emitted sounds similar to a steam-powered boat and were mentioned by most of those who kept journals. It is now covered most of the year by the waters of the reservoir.

Settling of Soda Springs by Morrisites

Soda Springs was settled in May 1863, by a group of refugees (morrisites; followers of Joseph Morris) fleeing from the Mormon-controlled Utah Territory. Morris, who was convinced that he was a prophet, had organized a communal settlement near the present site of Ogden and was preaching in open defiance of Brigham Young. Morrisites were active participants in the millennial dreams of nineteenth century America. They expected the imminent Second Advent of Christ and expected to take a leading role in the society that would be established after the second coming and that would last 1000 years.

|

A teenage Morrisite, Emma Thompson Just, described the trip to Soda Springs in May 1863. The letter reflects both the seductive beauty of an Idaho springtime and the naiveté of the Morrisite clan:

|

In June 1862, a Mormon territorial posse attacked the Morrisite settlement in Ogden. Joseph Morris was killed. The remnants of the movement, after their leaders were pardoned by the Utah territorial governor, realized they needed to flee.

In May 1863, two wagon trains, including 160 Morrisites, left Salt Lake City, led by Colonel Patrick E. Connor. In January, 1863 Connor had commanded the California militia which had perpetrated the massacre of Shoshoni Indians north of Preston at Battle Creek on Bear River. Connor was antagonistic to Indians and intended to subdue them, open the area to settlement, and to counter the expansion of the Mormons, who were viewed by him as disloyal to the Union cause during the Civil War.

U.S. Militia troops under Connor established a post at Soda Springs, on May 20, 1863. Morristown was built on the north bank of the Bear River about a mile below the present townsite of Soda Springs. It is now under Soda Point Reservoir.

But the climate at 5,800 feet, 1,600 feet above the Salt Lake Valley, was more severe than anticipated and agricultural productivity was low. Frosts during summer nights repeatedly killed crops. The settlement disbanded within 2 years. Most of the Morrisites became discouraged and left. Some of those who remained spearheaded the anti-Mormon movement in Idaho a decade later. The gravestone on p. 90 is for two who stayed in Soda Springs.

Mormon Colonization

In 1869, Brigham Young invested in 650 acres of land, including part of the present Soda Springs townsite. In June 1870, Young and a contingent of Mormons visited Soda Springs with an eye toward colonization. A lodging house for Young and his family was built overnight by 20 volunteers from Paris. Gold was discovered at Carriboo Mountain, north of Soda Springs, later that year. The first permanent Mormon settlers arrived in Soda Springs in the spring of 1871. Also in 1871, the Utah-Northern Railroad Company, a project of the Mormon church, was started north from Brigham City, headed for Soda Springs by way of Franklin, and ultimately to the mines near Butte, Montana.

A Wild Frontier Town

By the time Oregon Short Line Railroad Company reached Soda Springs in 1882, the town was a wild frontier community. It served as the railhead for a huge area of mountains and forest to the north, over which ranged miners starting in 1870, cattlemen starting in the 1880s, and sheepherders starting in the 1890s.

|

|

|

|

(left) Soda Point or Sheep Rock, looking east. Soda Point reservoir and city of Soda Springs are in the background. The Bear River here makes almost a 180° bend and flows southward into a canyon cut in Pleistocene basalt. Also at this point the Oregon Trail headed northwest while the Hudspeth Cutoff headed straight west across Gem Valley, (June, 1992). (center) Aerial view of Soda Springs, looking southeast, (June, 1992). Geyser is on the extreme right middle side of photo, one block west of Main Street, which runs diagonally through the right foreground of photo. Idan-ha' hotel stood east of Main Street, just north of the railroad tracks and west of the grain elevator. Soda Creek in foreground. (right) View looking east along Oregon Trail and U.S. Highway 30 just west of Soda Springs. Soda Point (alexander) Reservoir is on the right, and was the original site of the 1863 Morrisite settlement of Soda Springs. Union Pacific Railroad is just out of the view to the left. Oregon Trail followed a route just north (left) of the reservoir. Prominent scar between Oregon Trail and the Highway is a natural gas pipeline, (June, 1992). |

||

The Kackley Family

Doctor Ellis Kackley, fresh out of the University of Tennessee Medical School, came to Soda Springs in 1898, resolved to become "The Best Damn Doctor in the West". Many would say he succeeded (carney, 1990). He, his wife, Ida Sarver Kackley, and son, Evan, served the area for over 50 years, performing feats of frontier medicine by using ingenuity and common sense. He and Evan built the first Soda Springs hospital in 1925 to 1927. The hospital doubled in size to 40 beds in 1932. Ellis delivered over 4,000 babies.

Ellis Kackley died in November 1943, when Evan was in the Pacific during World War II. Twenty-five hundred people attended his funeral, which was held in the Soda Springs High School. His two large dogs created a commotion at the wake. Evan said his father would have enjoyed knowing that the dogs were still in control.

Butch Cassidy's Gang

Butch Cassidy and his band of outlaws frequented the Soda Springs area in the late 1890s, and had a camp in Star Valley, Wyoming. They, like some Mormon polygamists, found refuge in this isolated valley. Cassidy's gang robbed the Montpelier Bank of $16,500 on August 13, 1896, and escaped up Montpelier Canyon. An unmounted pack horse carried the loot out from under the nose of the posse.

On June 2, 1899, Cassidy's Gang robbed the Overland Flyer of the Union Pacific Railroad. Later that summer Dr. Kackley was asked to treat a wounded member of the gang that was holed up near Freedom, Wyoming. Both Kackley and Cassidy sympathized with underdogs and did not like the big corporations. Kackley brought the injured man to Soda Springs under cover of darkness and housed him close to the railroad. Another of the Cassidy Gang was disguised as a woman and took care of the injured man until he recovered.

Geology of the Soda Springs Area

Soda Springs is located near the trace of the Paris thrust fault, which separates the older, Late Proterozoic and Lower Paleozoic rocks of the Bear River Range from the younger Paleozoic rocks of the Preuss Range north and east of town. These younger rocks, belonging to the Meade thrust plate, contain the Permian Phosphoria Formation which is so important to the economy of the Soda Springs area.

Phosphate Mining

Phosphate mining began in the Soda Springs area in 1920 with an underground mine at Conda, named for the owner, Anaconda Copper Co. The Conda mine and townsite was officially abandoned on August 31, 1984.

Today the phosphate industry is the largest employer in the Soda Springs area, with several open-pit mines north and east of Soda Springs and large chemical processing plants on the north edge of town.

Reserves are large and demand is constant. Unlike the silver mining business, phosphate mining will be a strong industry for the foreseeable future. According to the Idaho Geological Survey, in 1990, Idaho's annual revenue from phosphate mining and processing was nearly $600 million. Silver mining produced about $70 million.

Anyone who has traveled U.S. Highway 30 through Soda Springs on a cloudy night will remember the ghostly red glow reflected off the bottoms of low clouds hanging above the molten slag piles near the Monsanto Chemical Plant north of the city.

Mineral Springs

The mineral springs in the Soda Springs area are charged with sulphur dioxide, calcium carbonate, and sodium silicate, products of their long journey through Paleozoic limestone bedrock. Formation Springs, northeast of town, has a large travertine terrace deposit.

|

|

|

|

(above) Abandoned townsite of Conda, looking north, (May, 1992). The streets remain but the houses have been removed. One of the open pits of the abandoned Conda Mine is to the right of the industrial buildings. The buildings served until 1991 as a loading facility for phosphate ore brought by slurry pipeline from the new Simplot mine at Smoky Canyon, about 30 miles east. The Conda mine began as an underground mine run by the Anaconda Copper Company, and was last operated by the J.R. Simplot Company. The dry tailings pond from the mine is behind the railroad tracks. The railroad cars are probably in storage. |

Monsanto elemental phosphorous plant north of Soda Springs. View looks east toward the Conda Mine. Highway 34 and the Union Pacific Railroad are just east of the plant, (May, 1992). | The Ballard Phosphate mine north of Soda Springs, operated by NuWest Industries, (October, 1992). |

|

|

|

| (bottom center)The municipally regulated geyser in Soda Springs looking south. Under normal conditions the geyser is allowed to erupt about every half hour, (March, 1996). | Warm waters of Hooper Spring, north of Soda Springs. The waters are naturally carbonated and are allegedly tasty for making root beer. In the 1890s the Idan-ha' Natural Mineral Water Company shipped bottled water from the Soda Springs area all over the world, (October, 1989). |

-

Carney, Ellen, 1990, Ellis Kackley, Best Damn Doctor in the West: Bend, Oregon, Maverick Publications, 283 p.

-

Carney, Ellen, 1992, The Oregon Trail: Ruts, Rogues and Reminiscences: Wayan, Idaho, Traildust Publishing Co., 332 p.

-

Haines, Aubrey L., editor, 1965, Osborne Russell's Journal of a Trapper: University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska, 191 p.

-

Johnson, Elaine S. and Carney, Ellen, 1990, The Mountain: Cariboo and other gold camps in Idaho: Bend, Oregon, Maverick Publications, 245 p.

Caribou Mountain Area

Grays Lake and Blackfoot Lava Field

Volcanic activity of the Blackfoot Lava field over the last million years has produced the large flat area north of Soda Springs. Rivers here wander slowly through marshes, as if they were wondering which way to escape the basin.

|

| Caribou Mountain and Grays Lake basin from the west, (July, 1992).The mountain is held up by granite stock intruded in Eocene time, about 45million years ago. Gold in placer deposits eroded from veins around the stock has lured prospectors to the area for over 100 years. |

Grays Lake has been an enclosed catchment area for water for at least a million years and contains a valuable record of pollen for the changing climates of Pleistocene time.

Lander Trail

The Lander Trail, named after F.W. Lander, who supervised its construction,went through the Grays Lake Valley. In the 1860s it became known as the Old Salt Road when salt was brought from Stump Creek to Montana, Boise and the west.

The Lander Trail was shorter than the Oregon Trail from South Pass to Fort Hall, but the hardships often extended the duration of the journey.Spring rains often made the trail impassable.

|

An admirer of the Lander Trail wrote:

|

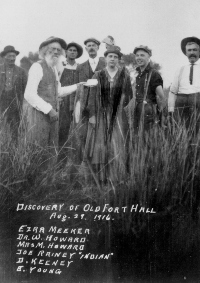

Discovery of Gold on Caribou Mountain

Gold was discovered on Mt. Pisgah (now Caribou Mountain) in 1870 by Jesse Fairchilds or "Cariboo Jack", an itinerant miner who gained his name in the Cariboo Mining District of British Columbia. A typical western gold rush followed. Two good-sized towns, Carriboo City and Keenan, grew up close to each other on the mountain, which looms above Grays Lake Valley to elevation 9,803 feet. Both cities were deserted after a few years but mining has continued sporadically to the present. About one million dollars of gold was taken from the area, mainly by placer methods, with the associated ditches and pipelines to supply water to the mines. Two hand-dug ditches,with a length of about 7 miles, rimmed Caribou Mountain.

|

|

|

| China Hat, a rhyolite dome, intruded about 100,000 years ago in the Blackfoot Lava Field north of Soda Springs. Immediately beyond China Hat is China Cap, and North Cone is to the north of it. Both of these are also rhyolite domes. View looks north to the Blackfoot Reservoir and Pelican Mountain. The town of Henry is just out of the photo in the right distance, (May, 1992). | ||

| Gold mines of Cariboo (carriboo or Caribou) Mountain, from Idaho Yesterdays, 1976, v. 19, no. 4, p. 10. Click on image for a larger view | ||

|

Report of Gustavus C. Doane's Military Expedition from Star Valley to Carriboo Mountain, December 16-22, 1876:

|

Chinese Miners

Chinese miners came to Carriboo in 1872 and were not excluded from the camp as they were in other Idaho mining camps. They were most numerous about 1880, and were generally acknowledged as being more skilled at mining than the Caucasians. The Chinese miners fled Carriboo in 1885 after a number of Chinese massacres in the west. In 1870 Chinese were the largest ethnic group in Idaho. Of the 4,269 Chinese, 3,853 were working as miners. That same year there were only 2,719 white miners in Idaho.

Freight to Carriboo Mines

Until 1871, freight traffic for the Carriboo mines came from Corinne, Utah,through Ross Fork (Fort Hall) and north of Grays Lake along the McCoy Creek drainage. From 1877 to 1878, Oxford was the railroad stop nearest the mines and in 1878, a stage road was established from Oxford through Soda Springs to the Carriboo Mining Region.

In 1878, the U & N railway reached Oneida (arimo). In 1882 the first Oregon Short Line railway train passed through Soda Springs and the town became the major center to supply the Carriboo Mines.

Old Williamsburg

Williamsburg, now almost totally abandoned, had in the 1870s, three dairies,a boarding house, saloon, school, post office and a summer tent city which included two prostitute tents. Today it is the site of management of the Kackley Ranches.

Demise of the Name Carriboo

In 1907, the U.S. Forest Service created Caribou National Forest, changing the name from Carriboo (or Cariboo) over the protests of the locals. The residents correctly pointed out that no Caribou had ever lived in the area.The incorrect spelling persists today, in the name of the National Forest and the County surrounding Soda Springs.

Polygamists in Star Valley Wyoming

Many of the original settlers of Freedom, Wyoming were Mormon polygamists who refused to give up their wives and families when Idaho and Utah enforced the Edmonds Anti-polygamy act of 1882, but Wyoming refused to do so. The name Star Valley comes from Starvation (Starve)Valley, a name the area gained during bitter winters in the late 1880s.Many cattle were lost in the severe winter of 1889. There were over 40inches of snow in two days and nights in March.

Cattle, Sheep, and Cranes

By 1875, large cattle herds were grazed in the Grays Lake area or passed through the area. Sheep became common in the 1890s. By 1894, 50,000 sheep summered north of Soda Springs. By the early 1900s that number had increased to over a million. Today much of the Grays Lake wetland area is part of a National Wildlife Refuge, and provides nesting sites for Sandhill and Whooping Cranes.

References

-

Anonymous, 1976, Gold Mines of Cariboo Mountain, Idaho Yesterdays, v. 19no. 4, p. 10-15.

-

Carney, Ellen, 1992, The Oregon Trail: Ruts, Rogues, and Reminiscences: Wayan, Idaho, Traildust Publishing Co., 332 p.

-

Codman, John, reprinted 1976, A Trip to Cariboo Mountain: Idaho Yesterdays,v. 19, no. 4, p. 18-24.

-

Derig, Betty, 1972, Celestials in the Diggings: Idaho Yesterdays, v.16, no. 3, p. 2-23.

-

Fiesinger,D.W.,Perkins,W.D.and Puchy,B.J.,1982, Mineralogy and Petrology of Tertiary-Quaternary Volcanic Rocks in Caribou County, Idaho, in Bonnichsen, Bill, and Breckenridge, R.M., editors, Cenozoic Geology of Idaho: Idaho Bureau of Mines and Geology Bulletin 26, p. 465-488.

-

Johnson, Elaine S. and Carney, Ellen, The Mountain: Carriboo and other Gold Camps in Idaho, 1990, Maverick Publications, Inc. P.O. Box 5007, Bend Oregon, 97708, 245p.

-

Mabey, Don, 1979, The Bend of Bear River. Bountiful , Utah, Horizon Publishers and Distributors, 136 p.

Gem Valley & Chesterfield

Gem Valley and Gentile Valley

The first settlers of the area between the Portneuf and Bear River Ranges(Gem Valley) were non-Mormons (Gentiles) who homesteaded in the southern end of the valley in the 1860s. The west side of the Bear River became known as Gentile Valley by 1875. The first three Mormon families settled in 1871 with impetus from Brigham Young, who was planning on the Utah-Northern Railroad Company coming through the southern end of the valley on the way to Soda Springs.

|

Oscar Sonnenkalb wrote, concerning Gentile Valley in the 1880s, that:

|

City of Grace

The first bridge across Bear River north of the present site of Grace was built in 1893, and the city was established shortly thereafter. Farming on the surrounding country was dependent upon irrigation efforts of the Last Chance Canal Company, which proceeded slowly and with great effort.In 1913, the Oregon Short Line completed the Grace Branch Line. In 1915,the village of Grace was incorporated. The village was named after the wife of the land agent in Blackfoot.

|

| Aerial view looking south at Grace, (May, 1992). The Utah Power and Light Company dam is in the left foreground, with the flume on an elevated trestle crossing under the highway to the right. Bear River occupies canyon cut in Pleistocene basalt. The East Branch of the Last Chance Canal winds east of town in the center left of the view. |

Last Chance Canal

Attempts to get water to the Grace area were unsuccessful between 1895and 1902. Although the Bear River ran just to the north, it was deep in a basalt canyon, and the water was inaccessible. Furthermore, Gem Valley's winters were harsh, and wooden flumes for canals using water from Bear River were repeatedly destroyed by winter snows. On March 4, 1897 the Last Chance Irrigation Co. filed for Bear River water and a dam site was selected a mile and half below Soda Point (Sheep Rock). Construction started in1898. The canal was opened in 1902-1904 and today provides water for farmland both north and south of Bear River on the upland around Grace.

The Last Chance Canal was built without federal assistance and without outside capital by local farmers, who worked cooperatively in the best spirit of the Mormon settlers. To provide footings for the dam, the farmers built log cribs of timber and rocks which they set on the ice-covered river in the winter. They hauled huge timbers 60 feet in length.

|

Fred Cooper who served as secretary of the Last Chance Canal Co. from1928 to 1961 said:

|

In June 1917, the Utah Power and Light Co. brought suit against Last Chance Canal Co. to get a decree on waters of Bear River and Bear Lake.Litigation of the suit lasted for three years until the Canal Company won the case with the Dietrich Decree of June 1920. This case adjudicated Bear River water for the first time.

Grace Power Plant

In 1906, L.L. Nunn and his Telluride Power Company moved in from Colorado and began construction of the a major hydroelectric plant on the Bear River, taking advantage of the 500 foot drop in the elevation of the Bear River between Sheep Point and the floor of the canyon west of Grace. In 1908, they finished a dam north of Grace above the elevation of the Lake Bonneville shoreline, with the power plant a few miles down the valley and 525 feet lower, on what had been the lake floor. At that time the plant was the largest hydroelectric station west of Omaha. At first the electricity was for use in the mining districts of Bingham, Utah and Eureka, Nevada; it was not sold to local customers.

The Telluride Power Company eventually became the Utah Power and Light Company. In 1915, the Grace plant was the biggest station on the newly integrated Utah Power and Light system.

Lake Thatcher and the Gem Valley Volcanic Field

Bear River makes nearly a 180° bend around Soda Point and runs south into southern Gem Valley and Cache Valley (mabey, 1979). However, as hypothesized in the 1963 Ph.D. dissertation of geologist Robert C. Bright, a native of Preston, the river's course prior to about a million years ago was probably north to near Chesterfield and then down the present Portneuf River canyon past Lava Hot Springs and to the Snake River west of Pocatello. At this time, Gem Valley drained to the north, much as Bear Lake Valley does today.

At times in the last million years the outlet of the ancestral Bear River became dammed and a lake, named Lake Thatcher, formed in Gem Valley. Volcanic activity of the Gem Valley volcanic field produced basalt lava flows which filled the north end of the valley, damming up the former Bear River course and forcing the river to turn south. The highest shoreline of Lake Thatcher was established at about 5445 feet elevation, after the lake was restricted to the southern part of the valley. Sediments deposited in Lake Thatcher underlie the farming country south of Grace and are recognized in water wells drilled as far north as Chesterfield. At its thickest point the Thatcher Formation is about 590 feet thick.

Some lava flows in northern Gem Valley were sourced from the Blackfoot lava field to the east. The lava flowed westward over the Chesterfield Range through Ten Mile Pass. Other main sources for lava flows were a fissure system that runs along the east side of the Gem Valley. The largest known lava tube is now an ice cave about 800 feet east of the cinder cone at Niter, south of Grace. About 600,000 years ago two basalt lava flows from northern Gem Valley ran down the course of the Portneuf River to Pocatello to form the Basalt of Portneuf Valley.

After Lake Thatcher occupied southern Gem Valley for perhaps several hundred thousand years, the Bear River drainage was captured, in Oneida Narrows, by south-flowing tributaries to Strawberry Creek and the Lake Bonneville basin. After Lake Thatcher drained southward into Cache Valley, the input of water from the Bear River plus a time of generally greater precipitation (a pluvial interval), caused Lake Bonneville to grow in the Great Salt Lake basin. The high level of Lake Bonneville,about 5,140 feet, reached into Gem Valley about 20,000 to 14,500 years ago. The shoreline was located just south of the site of the Grace Power Plant.

Chesterfield-Mormon Outpost in Idaho

Chester Call, a Mormon bishop from Bountiful, Utah, established a ranch near Chesterfield in 1879. Call convinced many of his relatives and friends to move to the new settlement.

|

Oscar Sonnenkalb wrote of Chester Call that he was:

|

Early settlers came to the Chesterfield area in 1881 and 1882 and built crude dugout shelters along the bottom land of the Portneuf River. The community was dealt a major setback in 1882, when the Oregon Short Line was built through Bancroft to the south, but the proponents of Chesterfield refused to believe this would doom their town.

in Wyndham, editor, (1986), Famous Potatoes |

Mormon Church authorities from Cache Valley visited Chesterfield in November, 1883, and advised that a townsite be laid out on high ground east of the Portneuf River flood plain. The townsite was a mile long and3/4 mile wide, and was divided into 10 acre blocks that would then be subdivided into four equal lots of 2.5acres. The settlers followed the pattern of Salt Lake City and laid out a city with streets ninety-nine feet wide, with sixteen foot sidewalks at each side. The streets of Chesterfield were wider than the boulevards of New York.

The site was named Chesterfield in memory of Chesterfield, England,and to honor Chester Call. Some families chose home sites in the village, but many did not. Prosperity came slowly, if at all.

Most of the buildings of Chesterfield were built between 1884 and 1904. By the mid-1890s 50 families had moved into the village. A kiln was built east of town to fire the bricks used to build new church buildings. By 1900, Chesterfield had 418 people on its ward records. A few brick homes were built, the pride of the community. The agricultural Depression of the 1920s and 1930s was the final blow to the city of Chesterfield.

|

|

|

|

(left) Aerial view looking north at Alexander Crater, a cinder cone on the Oregon Trail in Gem Valley. The Chesterfield Range is in the background,(September, 1984). (center) Aerial view looking north at the Chesterfield townsite. The ambitious town plat was never fully subscribed and houses were not built on many of the possible sites. The Moses and Mary Vashti Call Muir house is at the lower right. The Chesterfield Range is in the background, (May, 1992). (right) Moses and Mary Vashti Call Muir house, Chesterfield, (April, 1996). This is the oldest brick house in the Chesterfield area, built in |

||

Mormon Families in Chesterfield

Chesterfield, though today largely a ghost town, lives on in the spirit of the descendants of its Pioneers. The Chesterfield Foundation is dedicated to preserving the Chesterfield heritage, and has published the exquisite book "Chesterfield: A Mormon Outpost in Idaho."

Most Mormon farm families in the Chesterfield area were monogamous, though there were some polygamous households. Large families were considered an asset in Chesterfield, as in most Mormon communities; 8 or 10 children was a small family. Sixteen children was normal. Boys married at age 18 or 19 and girls at 16 or 17.

The history of Chesterfield's residents is a cycle of dreams and hard work to plow the sagebrush, followed by tragedy with the loss of land, crops, and livestock. Then the process would start over again, usually somewhere else. Chesterfield was always a cold and dry place. The farmers tired of watching summer storms pour a deluge on Gentile Valley to the south and miss their land. The knowledge that the Snake River Valley to the north was well watered through irrigation further disillusioned them. Most early settlers, including church leaders, eventually sold out and moved away.

|

Nathan James Barlow recorded the leaving of Judson Tolman, a polygamous Mormon Bishop, and his family. Tolman had been for three decades one of the pillars of the community.

|

|

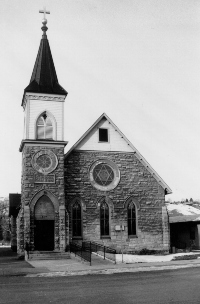

| Chesterfield LDS church and meeting house, dedicated August 23, 1892. Photo taken October, 1988. | |

|

The diary of Wanda Katie Whitworth, born in 1905, and who lived on a ranch about eight miles from Chesterfield, is quoted in Swetnam (1991,p. 61).

|

|

|

Farming in the Chesterfield area today mainly consists of large dry farms and ranches, operated by a few hardy survivors.

|

|

Lava Hot Springs Area

Hudspeth Cutoff

The Hudspeth Cutoff, after climbing high over the Portneuf Range south of the Portneuf River, wound down through Henderson Canyon and what is now the Lava Hot Springs golf course, to the river at a hill of Silurian dolomite known as Island Butte. The river formerly passed south of the Butte, but now flows only on the north side except in large floods. The dry channel can be seen from Highway 30. The Cutoff then headed up a small canyon south of the river and down into what became the rail station of Oneida and now is Arimo. From there it struck out west across Marsh Valley, crossing the Bannock Range south of Garden Creek Gap. Although this part of the Cutoff gained and lost considerable elevation, it was, at least, well-watered. The same cannot be said for the Cutoff west of the Bannock Range.

Mountain Man Bob Dempsey

Bob Dempsey, one of the last of the mountain men in southeastern Idaho,had a permanent camp west of Lava Hot Springs, where Dempsey Creek flows into the Portneuf. From 1851 to 1861, he trapped the mountains south of Lava, and effectively kept other trappers out. When the Hudson's Bay Company ceased operations in southeastern Idaho, Dempsey moved north to the Montana gold fields. Until 1915, the town of Lava Hot Springs was known as Dempsey, Idaho.

Lava Hot Springs and the Portneuf River

Lava Hot Springs was deeded to the state in 1902 to provide a health and recreation facility. The Lava Hot Springs area contains several hot springs which occur along a north-south normal fault southwest of town and an east-west normal fault which follows the Portneuf River canyon. The clear waters in gravel-bottomed pools at the state-operated resort make for a wonderful, relaxing visit. The east end of the pools are just as hot as a person can bear.

After the train depot was constructed in 1902-1905 the hot springs were accessible to the western traveler. The state built a natatorium in 1918 and now oversees operation of the swimming pools and hot baths through the Lava Hot Springs Foundation. The South Bannock County Historical Center located in the former Bank of Idaho building in Lava Hot Springs acts to preserve the heritage of the area.

On cold winter nights, when the steam of the hot springs reduces visibility to a few feet, people of all ages talk and play in perceived anonymity.Yet the city of Lava Hot Springs has been slow to take off as a recreational development. It has been for the last 30 years a quaint, tattered place, very much small-town southeast Idaho.

|

|

|

| (left) Ligertown, a ramshackle compound where dozens of lions, "ligers"(lion-tiger crosses), and hybrid wolves were kept (October, 1995). In September 1995 some animals attacked the owners and escaped. Several were shot and the owners were charged with numerous violations. The compound was destroyed in April, 1996.

(center) Postcard of Lava Hot Springs, looking south from U.S.Highway 30, 1942. Abe Lillibridge collection, Idaho State University. (right) Waterfalls along the Portneuf River west of Lava Hot Springs, (January 1984). The falls cascade down terraces of algally deposited travertine, and the calcium carbonate deposits of hot springs. |

||

Cache Valley

Geography

About half of Cache Valley is geographically in Idaho, but 80% of its people live in Utah. Logan, at the southern end of the valley, site of Utah State University and a Mormon Tabernacle, has historically been the center of commerce. The solidly Mormon agricultural towns of Preston and Franklin on the east side of the Bear River, and Oxford, Clifton, Dayton, and Weston,west of the river, are geographically and economically closer to Logan than to the Idaho towns of Malad City, Montpelier or Pocatello. This area was settled by Mormons who thought they were living in Utah Territory,and even in the 1990s, some Preston area residents see themselves as part of Utah, feeling that they have little in common with the politicians in Boise who collect and spend their tax money.

Geologically, Cache Valley is a graben, bounded by normal faults on both the east and west sides. On the east side is the Bear River Range, which passes into the Portneuf Range on the north side of the Bear River across the canyon at Oneida Narrows. These ranges contain mainly Late Proterozoic and Paleozoic bedrock (limestone and quartzite) above the Paris thrust fault, which is exposed on the east side of the Bear River Range. West of Cache Valley are the Bannock and Malad Ranges and the Wellsville Mountains in Utah, underlain by the same Paleozoic formations as well as Late Proterozoic strata beneath, including the Brigham Group and the Pocatello Formation.

Lake Bonneville

Cache Valley was filled with the northeastern arm of Lake Bonneville, and the lake flooded to the north through Red Rock Pass into Marsh Creek, the Portneuf River, and Snake River. The unconsolidated sands and silts deposited on the floor of Lake Bonneville form the surface of Cache Valley, and, when irrigated, make excellent agricultural soil. A network of canals, the trademark of lands settled by Mormon Pioneers, provide water to much of the valley.

|

Franklin

Franklin was the first settlement in Idaho, established by Mormon Pioneers in 1860. Clifton, Weston, and Dayton were established in 1864, 1865, and1867.

Lorenzo Hill Hatch was Bishop of Franklin from 1863 to 1875. His son was bishop from 1875 to 1907. He came west with the 1846 migration from Nauvoo, Illinois. Hatch married plural wives and was the father of twelve sons and twelve daughters. At the time of his death in 1900 he had 170 grandchildren and 32 great grandchildren.

Utah-Northern Railroad

The Utah-Northern Railroad Company, a cooperative project of the Mormon Church and local farmers, reached Franklin in 1874 and the Bear River at Battle Creek in 1876, but the company ran out of money. Utah-Northern shops had been built at Battle Creek, just south of the Bear River, at the site of Connor's Massacre.

The roadbed for the Utah-Northern Railroad, headed north to Soda Springs, was built toward Riverdale and Oneida Narrows, but tracks were never laid. It is still plainly visible near Johnson Reservoir north of Preston.

When construction was begun again (by the reorganized Utah & Northern Railway), the route headed north through Red Rock Pass to Marsh Valley and Pocatello.

Preston

Preston (originally called "Worm Creek' when it was founded in 1874), was located where it is because ground water, though alkaline, was shallow on the west banks of Worm Creek. In 1880, the name Worm Creek was changed to Preston, honoring Bishop Wm. B. Preston of Logan. Mormon leaders had, thankfully, objected to the word "worm." In 1881, the Cub River and Worm Creek irrigation system began. It was the first of several canal systems that would bring water to Cache Valley. In 1888, the townsite of Preston was surveyed and platted.

Logan Rapid Transit System

The Logan Rapid Transit system, consisting of inter urban trolleys connecting Logan to Ogden and northern Cache Valley, was organized in 1910 and reached Preston in 1915. The first timetable showed 16 trolleys daily, with the trip from Ogden to Preston taking 31/2° hours.The line was discontinued in 1947 and the material sold for scrap.

West Cache and Twin Lakes Canals

In 1899, the West Cache Canal, designed to water 17,200 acres on the west side of Bear River, was begun. The Twin Lakes Canal was begun in 1902 by enthusiastic farmers who were advised that the project would take 5 years and cost $282,000. Instead it took 20 years and cost $1,500,000.

Hot Springs

Natural hot springs exist along the Bear River at several locations north and west of Preston. The water is emitted along the trace of the normal fault which bounds the east side of Clifton Hill or Little Mountain east of Twin Lakes Reservoir. Commercial hot springs were operated at Old Bridge Porte just south of Battle Creek and at Riverview Sunset Del Rio Hot Springs half a mile downstream. Presently a hot springs complex at Riverdale is operated as a swimming pool.

|

|

|

|

(left) Headwall scarp of "Highway slide" which cuts the old alignment of U.S. Highway 91 north of the Bear River and Preston, (august, 1983). (center) Wide canyon of Bear River, looking east from the old grade of Highway 91, cut in unconsolidated sands and silts deposited in Lake Bonneville.The landslide shown in the upper photo on p. 99 is directly across the tree-lined course of the Bear River. Bear River Range in the background,(June, 1992). (right) Squaw Hot Springs building west of Preston. Building was vacant at the time of this photograph (June, 1992). It had been used in the past ten years as a greenhouse and a pig farm. Large travertine-coated open well flows water at 84° centigrade. |

||

Bear River Landslide Complex

Active rotational landslides exist on both banks of the Bear River north and west of Preston. These landslides represent response of unconsolidated Lake Bonneville silts, sands, and clays to the lowering of the base level of the Bear River after the drying up of the remnants of Lake Bonneville about 14,000 years ago. Installation of irrigation systems in the country both east and west of the river resulted in major landslides in the 1910s. Wet cycles of several years of duration with higher than normal rainfall have triggered periods of landsliding since then. The last period of active earth movement was in 1983-86. In 1993, the grade of U.S. Highway 91 was reconstructed to the west, away from the face of the hill, to avoid its former grade over a headwall scarp of one of these landslides.

Oxford

Oxford was settled in 1864. With completion of the Utah & Northern, the town became a mixed Mormon-Gentile community and aspired to replace Malad City as county seat of Oneida County. Oxford obtained the public land office in 1879 and a newspaper, the Idaho Enterprise, in 1880. Oscar Sonnenkalb lived there from 1881 to 1889.

Oneida County, in the 1880s, embraced 13 of the present counties of southeastern Idaho, extending 180 miles south to north from the Utah border to Montana, and about 100 miles east to west from the Wyoming border. The County Seat of this vast territory was first at Soda Springs, but in 1866,was moved to Malad City. However, as Malad City was far from the railroad, more than half of the county-officers resided and had offices in Oxford, on the narrow gauge railway.

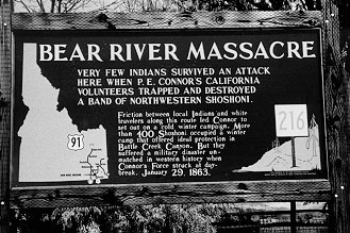

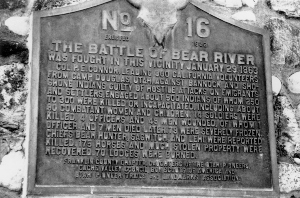

1863 Bear River Massacre

California Volunteers from Camp Floyd, south of Salt Lake City, annihilated between 240 and 300 Shoshoni Indians at the mouth of Battle Creek, north of Preston on a frigid morning, January 29, 1863. Only 23 soldiers were killed. The attack was led by Colonel Patrick E. Connor. Although the Mormon settlers had asked Connor for help, the attack was also motivated by Connor's desire to open the Bear River area to settlement by non-Mormons. Five months after the attack Connor led the Morrisites to Soda Springs. A decade of Indian skirmishes followed the Massacre, but the patterns of Native American hunting and settlement were effectively disrupted forever by this attack (madsen, 1985).

|

|

|

(above) Bear River Massacre Historical Marker, updated in the 1980s to the generally accepted account of the incident. It reads:

(above right) 1932 monument that paints the Bear River Massacre in a rather different light from the modern view. (right) 1953 monument; its emphasis is in keeping with the 1932 monument. |

Malad Valley & Country to the West

Hudspeth Cutoff

West from Marsh Valley the Hudspeth Cutoff crossed the Bannock Range, Blue Spring Hills, Deep Creek Range, and Sublett Range before reaching the Raft River Valley and joining with the California Trail near present-day Malta. Twin Springs, between present-day Rockland and Holbrook was one of the few reliable water supplies.

Pioneers chose the Hudspeth Cutoff in the great rush of 1849, when, sheeplike, they sought a more direct route to California. It is estimated that from June 20 to August 31, 1849, 250 wagons a day (an estimated16,000 to 25,000 people) traveled this route, even though it was unproven, more difficult, and as it turned out, did not save any time. The Pioneers were desperate to get to California first. About 45,000 traveled it in 1850 and 50,000 in 1852. The cutoff had a life of perhaps 10 years since few went that way after 1859, as the California gold fields played out. Arthur Hope's book "The Hudspeth Cutoff, Idaho's Legacy of Wheels" is a detailed account of the route.

Empty Country

The vast area from Malad City west to the Raft River Valley is mainly empty. There are few paved roads, and no gas stations. This is dry, sparsely settled country. Although much of it was homesteaded near the turn of the century, most of the farm houses were abandoned in the 1930s and the land is now divided into thousand-acre dry farms. The mountains are not high enough to catch significant winter snows and the streams in the valleys are small and unreliable. Extensive irrigation systems are not feasible. However, if most of these hardy farmers, who remain here, were given the choice, they would live nowhere else.

Geology of the Malad Area

The Wasatch fault runs along the east side of Malad Valley, and there are several active faults in the area to the south and west. Malad Valley is thus a half-graben, with the sedimentary valley fill generally tilted east.

The Bannock, Deep Creek, and Sublett Ranges as well as the Samaria and North Hansel Mountains are underlain by Paleozoic rocks, mainly limestones. These mountains are generally good fossil hunting country, with horn corals, brachiopods and gastropods easy to find if one knows the right place and is prepared to walk. There are several areas of limestone caverns. Air escaping from these caves on northern Samaria Mountain sometimes causes the mountain to "moan" in early spring.

Lake Bonneville extended north into the southern parts of Malad, Curlew and Juniper Valleys. Its shorelines can be seen if one looks closely, usually near the top of the level of plowed fields. They are generally more prominent in the southern parts of the valleys, closer to the Utah border.

Settlement and Brigham Young's Placement of the Utah Border

The first colonization of the Malad Valley, by Mormon cattlemen, was in the early 1850s. The settlers were recalled to Salt Lake City with the coming of the federal army of occupation (Johnston's army) to Utah in 1857-58. The first permanent settlement was in 1863. Malad City was settled mainly by Mormon converts from Wales.

Brigham Young came through the Malad Valley in 1855. Acting on the basis of astronomical observations by Orson Pratt, he marked the boundary line between Oregon and Utah territories as 108 miles from Salt Lake City, near the present town of Woodruff, Idaho. Although this placement was very close to correct, many Mormon settlers in Malad, Cache, and Bear Lake Valleys claimed that they were actually in Utah. The matter was not settled until the U.S. Government survey of 1872.

Early Malad City and Oneida County

Malad City grew up as a composite community in which Mormons, Gentiles, and Mormon apostates (the Josephites) dwelt without much friction. Soda Springs was the first county seat of Oneida County, which in the early 1860s included all of southeastern Idaho. Transportation from the Malad Valley to Soda Springs was difficult and the county seat was moved to Malad City in 1866. This move quieted hostilities between Malad Valley Mormons, who thought (or hoped) they were actually in Utah, and Gentiles. Oxford (in Cache Valley), served as the Federal Land Office until 1885, and many Oneida County officials lived there.

The Gold Road

In the early 1860s, two overland stage routes operated from Utah to the Snake River Plain and the mines in Montana. Both came north to Malad City. The Bannock Road split off up the Malad River and crossed into Arbon Valley to the mouth of Bannock Creek, and then north and east along the south bank of the Snake River. The more-used Portneuf Road, operated by stages owned by Ben Holladay, went over Malad Summit and to Marsh Valley, along the road followed by Interstate Highway 15 today. Holladay sold the Portneuf Road to William Murphy. In April 1870 Murphy was fatally shot in Malad City, by a deputy sheriff, after a dispute with county commissioners about how much he could charge. Leigh Gittins' book "Idaho's Gold Road" is a rich source of this history.

Josephites

In 1866 a splinter group of Mormons, led by one of the sons of Joseph Smith, came to Malad City, seeking a community far enough away from Salt Lake City not to cause friction but close enough to allow missionary work. They formed the Josephites, the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, which still exists.

|

| Grain elevator east of Twin Springs, along the Hudspeth Cutoff, (June, 1992). |

|

| Garden Creek Gap, looking west from west of Arimo. Garden Creek meanders through the narrow defile cut in hard east-dipping quartzite of the Scout Mountain Member of the Late Proterozoic Pocatello Formation. The stream is superposed, that is, it established its course on a cover of valley fill above the present level of the quartzite ridge. Vegetated stripes near the top of the slope north of the gap are normal faults, dropping the rocks down to the east, toward Marsh Valley, (august, 1982). Near here in July, 1994 supermodel Niki Taylor married Matthew Martinez, a McCammon man. Super-supermodel Cindy Crawford was among the wedding guests. |

Indian Settlement at Washakie

After the Bear River Massacre in 1863, the Shoshoni Indians, with help of the LDS church, made a permanent settlement in Malad Valley. Chief Sagwitch, wounded at the massacre, lived to join the LDS church and is buried at Washakie 2 miles west of the Malad River south of Malad City.

Holbrook

The Holbrook valley, only fifteen miles west of Malad City, but drier and less hospitable, was settled in 1878, 30 years after the Pioneers entered the Salt Lake Valley. But the big rush of homesteading did not come until about 1895. The main growth was 1901-1907.

Holbrook did not get electricity until 1946. Today its homesteads are largely abandoned. Dry farming for grain and cattle grazing are the primary agricultural activities.

References

-

Beus, S.S., 1968, Paleozoic stratigraphy of Samaria Mountain,Idaho Utah: American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin, v. 52, p.782-808.

-

Eliason, Carol, and Hubbard, Mary, 1987, Holbrook and surrounding areas history book 1878-1987: Holbrook, Idaho, 491 p.

-

Gittins, H. Leigh, 1976, Idaho's Gold Road: Moscow, Idaho, The University Press of Idaho, 165 p.

-

Haines, A.L., ed., 1965, Osborne Russell's Journal of a Trapper: University of Nebraska Press, p. 124.

-

Harstad, P.T., editor, 1972, Reminiscences of Oscar Sonnenkalb, Idaho Surveyor and Pioneer: Pocatello, Idaho, The Idaho State University Press, 66 p.

-

Hope, A.C., 1990, Hudspeth Cutoff, Idaho's legacy of Wheels: Idaho Falls, Idaho, Bookshelf Bindery and Press, P.O. Box 2204, Idaho Falls, Idaho, 222 p.

-

Howell, Glade F., 1960, Early history of Malad Valley: M.A. Thesis, Department of History, Brigham Young University, 130 p.

-

Kerns, G.L., and Kerns, R.L., Jr., editors, 1985, Orogenic patterns and stratigraphy of north-central Utah and southeastern Idaho: Utah Geological Association Publication 14, 328 p.

-

Link, P.K., and Smith, L.H., 1992, Late Proterozoic and Early Cambrian stratigraphy, paleobiology, and tectonics: Northern Utah and southeastern Idaho: in Wilson, J.R., editor, Field Guide to Geologic Excursions in Utah and Adjacent Areas of Nevada, Idaho, and Wyoming: Utah Geological Survey Miscellaneous Publication 92-3, p. 461-481.

Marsh Valley

Geography and History of Drainage

Marsh Valley, bordered on the east by the Portneuf Range and on the west by the Bannock Range, is the primary access to the Snake River Plain from the south. As the area was, after 1867, part of the Fort Hall Indian Reservation, legitimate settlement of the southern part was delayed until after 1889 when the land south of McCammon was excised from the reservation. Euro-American settlement of northern Marsh Valley began with the Land Run of 1902.

The Portneuf Range contains east-dipping Lower Paleozoic and Late Proterozoic rocks and the Bannock Range contains the same sequence, repeated across a normal fault that bounds the east side of Marsh Valley. The Basalt of Portneuf Valley is at the surface at the north end of Marsh Valley, having been erupted from the Bancroft area about 600,000 years ago.

The north end of Marsh Valley today contains an example of "inverted topography" with the lava flows filling the middle of the valley and the rivers confined to the sides. The Portneuf River is on the east and Marsh Creek, the main path of the Lake Bonneville Flood, is on the west. At the time of eruption of the lava flow, the center of the valley was lowest, and thus the term "inverted topography."

Geophysical surveys indicate that there is as much as 10,000 feet of valley fill underneath Downey, and that over the last few million years, drainage in Marsh Valley was primarily to the south, perhaps into a lake basin which periodically had an outlet to the Bonneville Basin. The prominent pediment surfaces seen below Scout Mountain and Mount Bonneville were established during this time of southward drainage and are graded to a base level several hundred feet above the present valley floor.

After establishment of the throughgoing drainage of the ancestral Bear River, the base level fell and the pediments were incised. Garden Creek which had been flowing east on deposits of gravel and sand began cutting down and encountered the bedrock ridge at Garden Creek Gap. It continued downcutting, resulting in the superposed canyon seen today.

|

Osborne Russell's thoughts on leaving southeastern Idaho for the Willamette Valley of Oregon in 1842.

|

Henry O. Harkness and early McCammon

Henry O. Harkness took over the operation of William Murphy's stagecoach service between Corinne, Utah and the Montana gold mines in 1870 and set up operations at the toll bridge over the Portneuf River at what is now McCammon (named for the man who negotiated purchase of the right of way for the Oregon Short Line Railway across the Fort Hall Indian Reservation). Harkness was an archetypal American entrepreneur of the late 19th century and a testimony to the power of the American Dream. In 1871, he married Murphy's widow Catherine, who had inherited her husband's property rights to land on the Fort Hall Indian Reservation.

In 1874, Harkness turned to ranching and purchased land at Oxford, just south of the border of the Fort Hall Indian Reservation. He also became partner in a bank in Corinne, Utah, which moved to Ogden in 1878. For his ranching endeavors Harkness imported the best stock and bred horses, cattle, and mules. He grew rich fields of potatoes and grain.

Henry and Catherine Harkness had no children. A year after Catherine's death in 1898, Harkness married her niece, Sarah Scott, who had come to care for Catherine during her last illness. Sarah bore five children. When he married for the second time Henry O. Harkness was 65 years old.

|

James L. Onderdonk, Territorial Controller for the Territory of Idaho, wrote, in "Idaho, Facts and Statistics" in 1885:

|

The building of the U & N Railway to Pocatello in 1878 saw the end of the freighting business and of steady use of Portneuf River toll bridge, but Harkness turned to other ways to make money. The Oregon Short Line railway bridges over the Portneuf River at McCammon were constructed near Harkness' bridge and farm. He built the grand and spacious Harkness House hotel to take advantage of the increase in traffic brought by the railroad. The chief competition was the Pacific Hotel, operated by the railroad in Pocatello, 25 miles away. By 1891, he had built a flour mill powered by waterfalls on the Portneuf. "We lead, others may follow" was advertised on bags of his flour. By 1893, the Harkness hydroelectric generating plant was established. Harkness expanded into the booming sheep business in the 1900s. In February 1905, he marketed a trainload of sheep in Chicago. In 1907, Idaho ranked third in the nation in amount of wool produced and fourth in size of flocks.

Bad floods occurred on the Portneuf River after January rains in 1911. The floodwaters destroyed some of Harkness' buildings and the stress brought on by the flood no doubt hastened his death in April 1911, at the age of 77. In June 1913, fire, a recurring scourge on the early towns of southeast Idaho, destroyed the Harkness House hotel.

Harkness' children moved away from McCammon and only remnant structures of the grand farm and ranch spread remain today.

Camp Downey

Although World War II was the most popular war in American history, a few people, because of religious convictions, refused to participate in an enterprise that involved killing one's fellow human beings. A Civilian Public Service Camp for conscientious objectors was established on 27 acres one-half mile east of Downey using what had been a Civilian Conservation Corps camp built in 1939 (Olinger, 1991). The camp consisted of 21 buildings and could hold 150 persons. It was operated by the Mennonite Central Committee, for the purpose of soil conservation and general farm work during manpower shortages caused by the war. The camp was closed in 1946, after the fall harvest.

Southern Bannock County

Residents of southern Bannock County generally have thought themselves separate from the dirty urban center of Pocatello. Before 1960 several towns had commercial centers, but the building of the Interstate Highway System of the 1960s and the decline of rail transportation produced the present system of people who live in the country, but go to Pocatello if they need to do some serious shopping.

Inkom & the Portneuf Narrows

The Gateway to the Northwest

The narrow canyon of the Portneuf River through the Bannock Range between Inkom and Portneuf Narrows is the geographic key to the development of southeast Idaho and the city of Pocatello. It was this water-level route that became the Idaho Gold Road followed by stages and freighters from 1864 to 1878, and then the route of the Utah & Northern and the Oregon Short Line railways. This was not, however, the route followed by the Oregon Trail.

The canyon was probably cut by the ancestral Bear River, on the order of a million years ago, in response to the subsidence of the area of the Snake River Plain near Pocatello after passage of the ancestral Yellowstone Hot Spot.

The canyon follows a line of weakness along the east-west Portneuf Narrows tear fault that probably formed in Cretaceous time during folding of rocks of the Putnam thrust plate. This tear fault passes north of the Portneuf River at Portneuf Narrows and separates rocks of the Late Proterozoic Pocatello Formation to the north and underlying Chink's Peak, that are structurally overturned, from correlative strata on the south side of the fault that are right-side-up.

The rocks exposed between the west side of Portneuf Narrows and Inkom span about 250 million years of earth history, that is from Late Proterozoic to Upper Cambrian time (750 to 500 million years ago). They thus were deposited during the development of complex invertebrate life forms which appeared on earth between about 610 and 540 million years ago. Several of the references cited at the end of this section discuss the complex geology of the Portneuf Narrows area.

|

|

|

(left) Column of basalt lava from the Basalt of Portneuf Valley near Inkom. Dark holes in the lava are vesicles or gas bubbles which exsolved out of the molten basalt. Basaltic lava tends to cool to six-sided columns as it shrinks during the change from liquid to solid, (June, 1989). (right) Portneuf Narrows from the southeast, looking west to Pocatello,(July, 1990). Gibson Mountain is on the horizon at the left, and Howard Mountain on the far horizon at the right. Late Proterozoic rocks of the Pocatello Formation are present north of the Gap, on the overturned limb of a large fold. Rocks of the same age on the south side of the gap are right-side up. The boundary is the Portneuf Narrows tear fault, which cuts through the small saddle about 1/3 of the way up the slope on the north side of the gap. |

|

Drainage History

In the Miocene, about 8 million years ago, the Yellowstone Hot Spot was located near Pocatello. The Pocatello-Blackfoot area was a high volcanic plateau, and drainage in the Inkom area was probably to the south. After the Hot Spot migrated northeastward and the former high plateau subsided, the direction of drainage was reversed. This was when the Portneuf Narrows was cut, by the ancestral Bear River. The gap was cut when streams began to flow north to what became the west-flowing Snake River, draining west in the wake of the east-migrating Hot Spot.

The floor of the Narrows had been lowered by 600,000 years ago to near the level of the present valley floor. Basaltic volcanic activity in Gem Valley, near present-day Bancroft, produced the Basalt of Portneuf Valley, which flowed down this canyon for about 50 miles, through the Narrows and to what is now Ross Park in Pocatello. Two lava flows can be distinguished.

The Bear River was diverted by these or associated volcanic eruptions to flow south into southern Gem Valley, and eventually to cut a passage at Oneida Narrows into the Lake Bonneville basin. The Portneuf River is thus the remnant of the ancestral Bear River.

The Lake Bonneville Flood

About 14,500 radiocarbon years ago, Lake Bonneville, which occupied much of the presently settled part of Utah, overflowed through a dam of alluvial fan material at Red Rock Pass at the north end of Cache Valley and produced the catastrophic Lake Bonneville Flood which scoured and cleaned loose rocks from the canyon west of Inkom. It is estimated that at Portneuf Narrows the floodwaters were 300 feet deep, (O'Conner, 1990).

The flood removed the Basalt of Portneuf Valley from the Portneuf Narrows area and deposited basalt Boulders which are common in parts of downtown Pocatello. The topography left behind by the flood is called scabland topography, and is manifested in dry waterfalls, alcoves, scoured bedrock surfaces, and Boulder bar accumulations along the flood path. Such topography is easy to see both south and west of Inkom.

The Abandoned Utah & Northern Railway Grade

The Utah & Northern narrow-gauge rail line followed a grade along Marsh Creek and generally on the south side of the Portneuf River through the canyon west of Inkom. It crossed the Portneuf River on a bridge that still exists near Blackrock and ran parallel to the present Union Pacific right of way through Portneuf Narrows.

Fort Hall Mine

Copper was mined in the 1890s and early 1900s in the Fort Hall Mine west of Portneuf Narrows. A railroad siding was built and a bunkhouse existed at the mouth of the canyon. In 1905 it is reported that Eugene O. Leonard, the founder of Idaho State University pharmacy school, made a trip to visit the mine, operated at that time by Henry Palmer. Leonard observed a rich vein of chalcopyrite Copper ore in one of the mine's drainage pits. This vein was covered up during subsequent operations, and even though 4,000 feet of tunnel were dug in the mine, its location was never found again.

Pocatello: The Gate City

Pocatello, initially a treeless sagebrush plain, carved from the Fort Hall Indian Reservation, settled by railroaders, owes its location directly to its geographic setting at the gateway to the Snake River Plain. Its layout was dictated by the railroad, around which the town was built. Its politics have reflected a never-affluent, pluralistic blue-collar town at the edge of Mormon country. These inherent internal conflicts have repeatedly stymied Pocatello's efforts to become prosperous. It has been a town without an upper class. In Idaho in the 20th century, things traditionally have come to Pocatello last. Now, in the 1990s, the prospect of growth and prosperity have returned.

Early Pocatello: The Townsite and the Indian Reservation

The early community of Pocatello, from 1882 until 1888, had to exist within the confines of the Oregon Short Line right of way because the Fort Hall Indian Reservation surrounded the area. Houses were erected along the west side of the railroad right of way, with prefabricated buildings moved in from railroad settlements at Omaha, Nebraska, and few from Battle Creek, Idaho, (north of Preston). Some were moved from Eagle Rock (Idaho Falls), to Pocatello in 1887. The townsite was too small and trespass on the Reservation was practiced by many. It was a tense situation.

There were not at first any churches in the community. A railroad official, who was a Mason, arranged for a school to be established in one of the railroad houses during the day; upstairs at night the first Masonic chapter in the area met and on Sundays a Congregational Church service was held.

Treaties and Enlargement of Pocatello

By the time the Treaty of May 27, 1887, was signed, which resulted in the Act of September 1, 1888, affirming the use of Indian lands by the Utah & Northern Railway Company and setting aside a townsite for Pocatello, Oregon Short Line Railway Company and Utah & Northern Railway Company together were occupying about 63 acres for right of way, shops and related facilities. An additional 150 acres were provided for by the Treaty. Included in the treaty and Act of Congress was recognition of the Utah & Northern right-of-way for which Oregon Short Line paid to the United States $7,621.04, at approximately $8.00 an acre. In addition, it paid $13,182.72 for the additional right-of-way and land acquired under the Treaty.

Also included in the 1888 Act of Congress were almost 50 acres for a reservoir and pipeline from City Creek to the railroad right of way. This right-of-way reverted to the U.S. Government in 1992, and a parkway, connecting downtown with the Portneuf Greenway system was constructed, starting in 1996.

Surrounding the railroad premises was the townsite of Pocatello, consisting of 1,840 acres, less the land occupied by the railroads. The townsite plat contained no park land and did not acknowledge that the Portneuf River meandered through its flood plain in the middle of town. The river is not indicated on the plat. The individual lots contained in the townsite were surveyed and sold at public auction in 1891, though it was understood that persons already in possession were to have first choice. Under the 1888 Act, lots not sold at auction became part of the public domain, subject to purchase by the public. Accordingly, permanent buildings began to be erected throughout the townsite prior to the 1891 auction. Photographs of downtown Pocatello taken in 1889 show many large, permanent buildings. Even after the auction, there was an almost immediate need for the new town to expand, but it could not because the lands surrounding the townsite were reservation property.

Reduction of Area of the Fort Hall Indian Reservation

The original Fort Hall Reservation had approximately 1,500,000 acres; the first reduction was contained in a treaty entered into between the Indians and the government in 1880 but not ratified by Congress until February 23, 1889, restoring the southern one-third of the reservation to the public domain.

The Oregon Short Line right of way was sold in 1882. Pocatello townsite and the Utah & Northern right of way were removed in 1888. The next major reduction was by an 1898 treaty, which was ratified in 1900, removing the middle third of the Reservation upon proclamation by the president. This proclamation was issued by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1902, causing a land rush in the area surrounding Pocatello and south to McCammon.

Rapid Growth in the 1890s

Although the townsite had not yet been surveyed nor the lots sold, a government was provided for the future town by the commissioners of Bingham County on April 29, 1889. In 1889 the two railroads merged, becoming known as the Oregon Short Line and Utah & Northern Railway Company. Growth was rapid and by 1893, a new county, Bannock, was carved out of Bingham County by the State Legislature, with Pocatello as its county seat.

Southwest is West; Southeast is South

The railroad line ran through Pocatello townsite in a south-easterly to north-westerly direction and when the streets of Pocatello were laid out, they followed the railroad configuration, resulting in some confusion throughout the years. We follow custom in this book, referring to the northwest-southeast streets as running North-South, and the northeast-southwest streets as running East-West.

The Legacy of No Urban Planning

In his reminiscences of life in territorial Idaho just before statehood, Oscar Sonnenkalb, a surveyor and civil engineer, commented on the layout of Pocatello with vitriolic language. The practice of building on either side of the railroad established, in effect, two competing villages, laid out without regard to drainage, natural barriers or the desirability of providing streets where buildings would have the "desirable equal chance for morning and afternoon sunlight."

Visitors often comment on the narrow streets of Pocatello, but both Pocatello and Idaho Falls were laid out with them. That was the norm in city planning at that time. The lack of park land along the river banks has remained a blight on the ambiance of downtown Pocatello.

|

Pocatello Townsite, Sonnenkalb charged, was laid out with little foresight because the plans were not worked out by practical civil engineers but by clerks in the Land Office,

|

|

|

|

(left) View looking west on West Center, about 1890. The Hub Building is on the right hand side. The next cross street is Main (then Cleveland Avenue). The Pioneer Building is southeast of the intersection of West Center and Main. Bannock County Historical Society Collection. (right) View of the 100 block of South Main Street looking north, August 1913. Both horse-drawn and internal combustion vehicles are on the street. The Nicolet (Whitman) Hotel occupies the tall light-colored building. The Palm Cafe (originally the Wrensted Building) to the right of the hotel was destroyed by a windstorm in June, 1992. The site was rebuilt in 1993 as the Continental Bistro. The Pioneer Building is on the southeast corner of Center and Main. In 1996 the downtown U.S. Post Office branch was relocated there. The Petersen Furniture building can be seen in the distance on the east side of Main. This street was, until 1906, called Cleveland Ave., but the name was changed because of retrospective political animosity toward the Democrat, the only man to be twice President. Bannock County Historical Society Collection. |

|

Naming the Streets of Downtown

The matter of naming the streets tells us something of the political character of the early town. At the outset, streets paralleling the railroad were named for presidents, beginning with the current president, Harrison, next to the right-of-way, and moving westerly by earlier presidents in a reverse order, that is, Cleveland, Arthur, Garfield and so forth. The equivalent streets east of the railroad were given number designations, viz. 1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc. East-west cross streets on both sides of the tracks were given letter designations, A, B, C, etc.

By 1906, the growing municipality felt the need to require the numbering of buildings to facilitate "free" mail delivery and to give some streets more appropriate names. The east-west street designations were changed from letters to the names of early explorers, trappers, generals, railroad officials and the like, which names they still bear. One American president was slighted in the naming of Pocatello's streets. As already noted, the street next to Harrison was Cleveland. In 1906, a Republican city council responded to a petition signed by every merchant along Cleveland Avenue by changing its name to Main Street. Not only that, but in later years a plat annexed to the north side of town bore the names of the presidents following Harrison, and although the next president in time was Cleveland, the new plat picked up the president names with McKinley, so that the man who was president twice does not have a street named after him in Pocatello.

Dusty Streets and a City Divided

The problems faced by the young town were those of all frontier communities. The fine loess soil produced clouds of dust when wagons rolled over dry streets. The streets were not paved so it was necessary to water the streets to keep the dust down. However the city water supply was privately controlled and little water was made available for this purpose. Sidewalks were slow in coming.

The only way to cross the tracks between the two sides of town was by using at-grade crossings. Because of the number of trains using this busy terminal, it was hazardous to cross the tracks, especially for school children. Coal smoke from steam engines was always in the air and cinders found their way into every nook and cranny.

|

|

|

(left) Early 1920s postcard of Main Street, Pocatello, looking north near the intersection with Lewis. On the left is the Benson Hotel. On the right is the present Station Square, then the Fargo-Wilson-Wells Department Store, which housed the bus depot and the Western Union office. Bannock County Historical Society Collection. (right) View looking north from East Center Street at the Bannock County Courthouse in foreground and Bonneville School in background, about 1903. Note the lack of trees. The Courthouse was built in 1902, added onto in 1913 and razed in 1955. It occupied what is now the parking lot of the new courthouse, which was built in front of it. The school (on the present site of the U.S. Post Office) was built in 1895 and razed in the early 1960s. The Bear Lake County Courthouse (still standing in Paris) has the same architectural design as the old Bannock County Courthouse. Bannock County Historical Society Collection. |

|

Pluralism

At the turn of the century "Downtown" was on the west side of the tracks, as were the best residences and several churches. On the east side there were more commercial establishments, many being of a kind not desired on the west side, such as the "walled city" red-light district, a number of saloons and houses of minorities. Being a railroad town, in the 1910s and 1920s Pocatello became a city of cultural diversity with communities of Blacks, Greeks, Italians, and Chinese. This mosaic flavor remains today, with the addition of University Professors.

|

|

|

|

(left) East end of Center Street Viaduct, spring 1914. Note the Mansard Roof of the Pacific Hotel, which had to be partly destroyed to make way for the viaduct. The old freight depot is north of the Pacific Hotel, with the peaked roof. The right angle bend was required by East Center Street merchants who feared they would be cut off from business if the east slope of the structure were continued to street level. Pocatello economic development has always been difficult, and sometimes stupid decisions had lasting impacts. This was one. Bannock County Historical Society Collection. (center) View of West Center Street from Center Street Viaduct, August, 1915. The automobile had taken over personal transportation from the horse. The Kane Building, built in 1915, is the white brick structure on the south side of West Center. The hand written date on the photo is incorrect. Bannock County Historical Society Collection. (upper right) West side of Center Street Viaduct over the Union Pacific tracks, summer 1912. This viaduct was the source of the term "going over town." Note the Indian riding a horse accompanied by his dog on the sidewalk. Three early motorcars are on the crest of the bridge. The Pacific Hotel (reduced in size) can be seen north of the viaduct. Bannock County Historical Society Collection. |

|

|

| Parade with Santa Claus at the head on the west side of the Center Street Viaduct, December, 1913. Picture taken from the corner of Center and Main. The Hub Building is on the left, and the Pioneer Building is on the right. Bannock County Historical Society Collection. | ||

The Center Street Viaduct

The Center Street Viaduct and the Halliday Street Subway were built in 1911 by the Union Pacific Railroad, on contract to the city of Pocatello, to allow traffic to cross the tracks without danger or interference with railroad operations. The viaduct opened Oct. 3, 1911, and the subway in August, 1911. The viaduct was replaced with the present subway in 1934.

Congregational Church