Geography

Geography Basics

How Did Idaho Get Its Name?

Originally suggested for Colorado, the name "Idaho" was used for a steamship which traveled the Columbia River. With the discovery of gold on the Clearwater River in 1860, the diggings began to be called the Idaho mines. "Idaho" is a coined or invented word and, despite popular folklore, is not a derivation of an Indian phrase "E Dah Hoe (How)" supposedly meaning "gem of the mountains."

What is the Highest Mountain in Idaho?

Mount Borah in the Lost River Range is the highest mountain in Idaho at 12,662 feet above sea level

|

|

What is a GIS?

In brief, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) is a state-of-the-art computer methodology for organizing and analyzing spatial, map-based data. Unlike other cartographic tools, GIS integrates map making with database management and statistical analysis. Results can be summarized in tables or reports, and displayed as maps. With a few commands, vast amounts of data can be summarized in visual, easily understood formats. GIS is widely used to query, analyze, and map data to support decision-making. GIS has become a fundamental tool for agricultural managers, scientists, land-use planners-and analysis and problem solving. Today, GIS is a multi-billion-dollar industry employing hundreds of thousands of people worldwide.

What is a GPS?

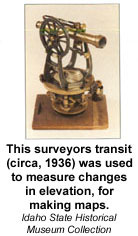

Many maps, such as road maps, only deal with the two-dimensional location of an object without taking into account its elevation. While convenient, these maps do not accurately represent the surface of the earth. The earth is contorted ("relief"), and because of this latitude, longitude and elevation are necessary to locate areas exactly on a map (three-points, or "triangulation" is required to accurately locate something within 3-Dimensional space). Maps that deal with three dimensions are called topographic maps. Topographic maps take into account the elevation of the area being mapped above a ‘reference datum’, thus showing the actual shape of the area.

Photographs, satellite imagery, surface and subsurface scientific exploration and other means of gathering data have changed the way modern maps are constructed. Recent computer technologies have allowed for the development of Geographic Information Systems which provide complex pictures of the earth - both on the surface and beneath it. The global address of any place on earth includes both latitude and longitude. This coordinate system is widely used in all areas of navigation and related technologies. An example is Global Positioning System technology which uses a receiver to transmit a signal to satellites orbiting the earth. The GPS unit then uses the amount of time it takes for the satellite to receive its signal, and the satellite's' position in the sky to calculate an exact latitude and longitude.

Understanding Topographic Maps

A topographic map, simply put, is a two-dimensional representation of a portion of the three-dimensional surface of the earth. Topography is the shape of the land surface, and topographic maps exist to represent the land surface. Topographic maps are tools used in geologic studies because they show the configuration of the earth’s surface. Cartographers solve the problem of representing the three-dimensional land surface on a flat piece of paper by using contour lines, thus horizontal distances and vertical elevations can both be measured from a topographic map.

General Information

The terms below indicate what information is contained on a topographic map, and where it can be found.

Map Scale: Maps come in a variety of scales, covering areas ranging from the entire earth to a city block (or less).

Vertical Scale (contour interval): All maps have a horizontal scale. Topographic maps also have a vertical scale to allow the determination of a point in three dimensional space.

Contour Lines: Contour lines are used to determine elevations and are lines on a map that are produced from connecting points of equal elevation (elevation refers to height in feet, or meters, above sea level).

The following are general characteristics of contour lines:

1. Contour lines do not cross each other, divide or split.

2. Closely spaced contour lines represent steep slopes, conversely, contour lines that are spaced far apart represent gentle slopes.

3. Contour lines trend up valleys and form a "V" or a "U" where they cross a stream.

On most topographic maps, index contour lines are generally darker and are marked with their elevations. Lighter contour lines do not have elevations, but can be determined by counting up or down from the nearest index contour line and multiplying by the contour interval. The contour interval is stated on every topographic map and is usually located below the scale.

Creating topographic profiles: Remember that topographic maps represent a view of the landscape as seen from above. For producing a detailed study of a landform it is necessary to construct a topographic profile or cross-section through a particular interval. A topographic profile is a cross-sectional view along a line drawn through a portion of a topographic map.

A profile may be constructed quickly and accurately across any straight line on a map by following this procedure:

a. Lay a strip of paper along a line across the area where the profile is to be constructed.

b. Mark on the paper the exact place where each contour, stream and hill top crosses the profile line.

c. Label each mark with the elevation of the contour it represents.

d. Prepare a vertical scale on profile paper by labeling the horizontal lines corresponding to the elevation of each index contour line.

e. Place the paper with the labeled contour lines at the bottom of the profile paper and project each contour to the horizontal line of the same elevation.

f. Connect the points.

Stream Gradient: Stream gradient can also be determined from a topographic map. The gradient of a steam or river is determined by measuring a section of a stream or river and dividing the distance (in miles) into the vertical difference (in feet) between the two points. The result is expressed in feet per mile (ft./mi.). The equation used is:

|

Gradient =

|

drop in elevation between two chosen points (feet) |

| distance between the two points (miles) |

Tips for Interpreting Topographic Maps

Vertical exaggeration: Vertical exaggeration is the effect that is created when the horizontal and vertical scales on your topographic profile are not the same.

Determining hillslope: Among other things, a topographic map can be used to measure the average slope of a hill (or hills).

|

| Click on image for a larger view. |

Topographic Map Example

As an example, look at a map of the Sulphur-Boundary Creek area along the Middle Fork of the Salmon River This map is a geologic map of glacial geology in the area, drawn on a topographic map base. The map has a contour interval of forty feet, which means that every place between the marked 6800 foot line and the next lowest line (which is 6760 feet, and not marked) has an elevation equal or greater than 6760 feet, but less than 6800 feet. You can figure out the elevation of any point by finding the nearest labeled line, counting the number of lines above or below it, multiplying by the contour interval, and adding or subtracting the result from the nearest marked contour line. The more closely spaced the contour lines, the steeper the slope. You can find out exactly how steep the slope of the area you are interested in by subtracting the lowest elevation from the highest, and dividing the result by the horizontal distance. Horizontal distance is found on the scale. As you look at the map, notice that the contour lines enclose smaller and smaller areas. The smallest circles represent the tops of peaks, and some are marked with x’s with numbers next to them. The numbers are the elevation at the top of the peak.

Follow a contour line along its length. Notice the indentations. As the contour lines cross gullies or stream drainages, they "vee" uphill. Drainages that have water in them year-round have solid lines connecting the points of the vees. Drainages that have water only part of the year are marked with dashed lines.

Maps & Globes

|

|

| Remember: Earth is tipped on its axis of rotation (relative to our plane of orbit around the sun). |

A map is a way of representing an object’s (or objects’) real-world location on an artificially created two-dimensional surface. Maps have been used by humans since about 1400 B.C. when they appear in the archaeological record of the ancient Egyptians. Later, as their cultures mixed, these early attempts were improved upon by the Greeks. In 150 A.D. Ptolemy (an Egyptian) added the first lines of latitude and longitude used on a map. Today typical references used for mapping include latitude, longitude, the location of the north and south poles, and the location of the equator.

Latitude and Longitude are cartographic lines superimposed on the surface of the earth. These lines create a grid coordinate system that is used to pinpoint locations on earth - each point on the globe is assigned an unique pair of longitude and latitude values so that it may be identified easily and accurately. Latitude lines (or parallels) run from east to west horizontally around the globe. Longitude lines (or meridians) run vertically from the North and South Poles.

Like other circles, latitude and longitude are measured in units of degrees, minutes, and seconds with a total of 360 degrees possible (1 degree = 60 minutes and 1 minute - 60 seconds). A protractor can be used to measure these distances.

Longitude values range from 180 degrees west to 180 degrees east, and are measured from the Prime Meridian, or zero degrees longitude (the longitude line passing through Greenwich, England). The longitude line directly opposite to the Prime Meridian is called the International Dateline and can be considered as either 180° east or west). The Equator is the line of latitude that divides the globe into two equal halves, the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. The Equator is designated as 0° latitude. Latitude is measured North or South of the Equator with a range of 0 to 90 degrees. Latitude lines below the equator have negative values, while those above the equator have positive values. The full range of latitude values then is -90 (S) to +90 (N) degrees. Some familiar examples:

1. The Tropic of Capricorn (23.5 degrees S)

1. The Tropic of Capricorn (23.5 degrees S)

2. The Antarctic Circle (66.5 degrees S)

3. Tropic of Cancer (23.5 degrees N)

4. The Arctic Circle (66.5 degrees N).

Look at how the curvature of the earth affects the shape of the latitude and longitude lines. All of the longitude lines are identical so degrees of longitude are constant, always covering the same distance (about 60 nautical miles). In contrast, degrees of latitude vary. Near the equator, a degree of latitude is approximately 60 nautical miles, but as you approach the poles that distance goes to zero.

It is important to keep in mind that the earth is curved and maps are flat, so they do not quite represent reality. To properly map the earth, a planet shaped globe is required. Cartographers represent the curvature of the earth on a flat surface by means of a projection. Regions are projected on to a map in different ways in order to correct for real direction, area or shape. The most common projection used is the Mercator, which was invented in 1568 by the German Gerhard Kramer (a.k.a. Gerardus Mercator). The Mercator distorts the size of the continents however because it makes the earth the same width at the at the equator and the poles.

The Data Behind a Map

Reference Datum: A reference datum is a known and constant surface which can be used to describe the location of unknown points. On Earth, the normal reference datum is sea level. On other planets, such as the Moon or Mars, the datum is the average radius of the planet.

Map Projections: A map projection is a way of representing the 3-dimensional surface of the Earth on a flat piece of paper.

Distortion: Each of the different types of projections have strengths and weaknesses, and knowledge of the advantages and disadvantages of a particular map projection will often help you to choose what map you want to use for a particular project.

Grid systems: A grid system allows the location of a point on a map (or on the surface of the earth) to be described in a way that is meaningful and universally understood.

Coordinate systems: There are several types of grids (a.k.a. coordinate systems) used to divide the earth’s surface. Four of these are in common use on maps published in the United States: geographic, universal transverse mercator (UTM), state plane, and public land survey coordinate systems.

Much of the information discussed above is applicable to all types of maps.

Fun Facts:

Can You Really Get Sugar from a Sugar Beet?

Sugar is manufactured from the roots of the sugar beet, the leaves and tops being removed after harvesting and used as stock feed. The roots are cut into cossettes, or chips, at the sugar factory, and the cossettes are crushed to remove the juice. The pulp remaining after the extraction of the juice is a rich food for domestic animals.

After extraction, lime is added to the juice; the remainder of the process is similar to sugar production from sugarcane. Beet molasses is fed to livestock; table molasses is not made from beets because of difficulties in purification. The sugar that is produced from the sugar beet is chemically identical to the sugar that is derived from the sugarcane.

What Was a Pioneer Frisbee?

If you think frisbees were invented in the 1960s, you're wrong--by about a hundred years. Children on the Oregon Trail threw frisbee-like devices back in the mid-1800s. But they weren't made of plastic--they were made of buffalo dung.

During the great western immigration, the entire Great Plains region was covered with buffalo chips--they were unavoidable. And yes, kids occasionally tossed them about in a frisbee-like manner. But the chips had a much more practical purpose for the emigrants--they were burned for fuel.

There was no firewood along much of the Trail, so the only alternative was dried buffalo dung. Even though the pioneers were hardy, they didn't much enjoy gathering up bushels of chips every night.

The chips burned surprisingly well, and produced an odor-free flame. Usually, each family had its own campfire, but sometimes everyone contributed their chips for one big bonfire.

Idaho Demographics

The state of Idaho has a long-standing reputation as a place of legends and change set in the midst of breathtaking landscapes. Wide-open deserts give way to forests and to towering granite mountain peaks. Pioneers, entrepreneurs, Native Americans, Explorers, Gold, High-Tech, High-Adventure...Idaho has a little of everything - a fact reflected in its rich natural history and demographic profile. The state is home to the theater, opera, ballet, symphonies, festivals, carnivals, rodeos, and more. Celebrations occur year-round, in every region. Many are imbued with regional and historical flair and follow traditions that date to Idaho's Native Peoples and earliest pioneers. Sporting and other outdoor events are commonplace.

Three major universities exist as a part of the Idaho higher education system: Idaho State University; the University of Idaho, Moscow and; Boise State University.

Scientific research and inquiry into the natural history of Idaho is of great importance at all three institutions, as well as at the Idaho Museum of Natural History, the Idaho Geologic Survey and other organizations around the state.

The United States Forest Service plays a significant role in the state as well. They manage and study a large percentage of Idaho's forests in addition to large areas of rangeland. The BLM also manages and studies Idaho Rangelands. Both agencies employ large numbers of Idahoans.

Agriculture and timber-related industries are also significant employers, as are the mining industries. Hi-tech industry is one of the fastest-growing in the state (centered in the Boise metropolitan area).

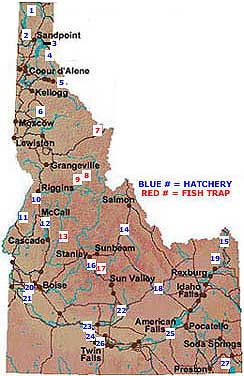

DOE's Idaho Engineering and Environmental Laboratory (INEEL) is another significant resource for the state. As are the recreation and tourism related industries such as Idaho's Fisheries.

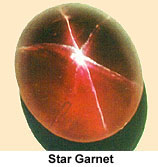

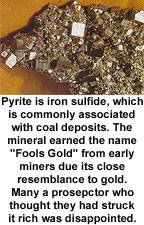

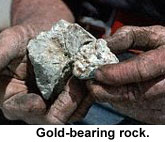

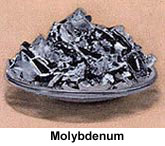

Significant natural resources found within Idaho boundaries include: timber, water, silver, lead, phosphate, gold, molybdenum, sand, gravel, building stone, limestone, copper, garnets and zinc.

Primary agricultural industry products include: potatoes, hay, wheat, sugar beets, cherries, peaches, beef, dairy products, apples, hatchery trout.

The most important manufactured goods produced include: french fries, sugar, canned fruit and vegetables, particleboard, computers, farm machinery and supplies, paper products, phosphate fertilizers.

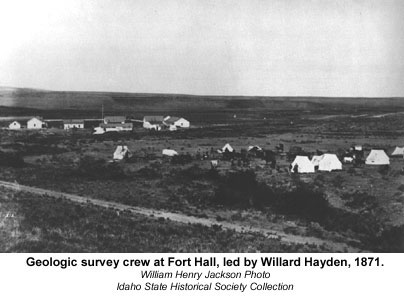

Maps, Surveys & Boundaries

The principal meridians and base lines of the west are a product of the Northwest Ordinance of 1785. This measure provided for the orderly survey and sale of public lands. During the colonial period, New England had disposed of public lands by surveying them first and then selling them in orderly blocks. A system of "indiscriminate locations and subsequent survey" prevailed in the southern colonies. This permitted settlers to lay out the land they desired where they wished and then have it surveyed. The southern system led to conflicting titles as pioneers laid out irregularly shaped plots to claim the most fertile land and made it impossible for the government to dispose of the less desirable tracts. The survey of public lands was originally evolved in Ohio and was well developed by the time the West was settled.

The Ordinance of 1785 provided that the public lands of the United States be divided by lines intersecting true north and at right angles to form townships and ranges - both six miles square. The townships and ranges were to be marked with progressive numbers from the beginning, or "initial" point that was surveyed in a given area. Such townships and ranges were to be divided into thirty-six sections, each one mile square and containing 640 acres. The sections were to be numbered respectively, beginning with the number one in the northeast section and proceeding west and east alternately through the township with progressive numbers to thirty-six.

The Ordinance of 1785 provided that the public lands of the United States be divided by lines intersecting true north and at right angles to form townships and ranges - both six miles square. The townships and ranges were to be marked with progressive numbers from the beginning, or "initial" point that was surveyed in a given area. Such townships and ranges were to be divided into thirty-six sections, each one mile square and containing 640 acres. The sections were to be numbered respectively, beginning with the number one in the northeast section and proceeding west and east alternately through the township with progressive numbers to thirty-six.

Note that townships are counted north-south of the initial point, while ranges are counted east-west.

In order to complete this type of surveying task, it was necessary to establish independent initial points to serve as bases for surveys. Principal meridians (north-south lines) and baselines (east-west lines) were then surveyed from these initial points. Guide meridians were initiated at baselines, and standard parallels were initiated at principal meridians to form townships.

In Idaho the Initial Point is located about 8 miles south of Kuna. It is a volcanic hill that was precisely located on April 19, 1867. Peter W. Bell used stellar observations to locate the point, by order of Lafayette Cartee, the first surveyor general of Idaho Territory. The Initial Point is marked with a small, round brass marker (about the size of a jam jar lid), and the hill is visible for miles around.

In Idaho the Initial Point is located about 8 miles south of Kuna. It is a volcanic hill that was precisely located on April 19, 1867. Peter W. Bell used stellar observations to locate the point, by order of Lafayette Cartee, the first surveyor general of Idaho Territory. The Initial Point is marked with a small, round brass marker (about the size of a jam jar lid), and the hill is visible for miles around.

The principal meridian for Idaho is the exact north-south line as measured at Initial Point. It was called the Boise Meridian, and it runs the entire length of Idaho - from the Nevada border to the border with British Columbia.

The city of Meridian was named for the Boise Meridian as it lies exactly north on the surveyors line.

All surveys conducted in Idaho which divided the almost 54 million acres of unmapped lands are based from Initial Point.

State Symbols of Idaho

|

Land Area: Water Area: Highest Point: Lowest Point: Length: Width: Geographic Center: Number of Lakes: Navigable Rivers: Largest Lake: Temperature Extremes: Population (as of 1995): Land Ownership: State Folkdance: |

State Insect: State Fish: State Bird: State Horse: State Flower: State Tree: State Fossil: State Gemstone: State Song: Here We Have Idaho

There’s truly one state in this great land of ours,

|

Public Lands & Recreation Areas

The Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation has historically utilized its enabling legislation (Idaho Code 67-4219) as its mission statement: "It is the intent of the legislature that the department of parks and recreation shall formulate and put into execution a long range, comprehensive plan and program for the acquisition, planning, protection, operation, maintenance, development and wise use of areas of scenic beauty, recreational utility, historic, archaeological or scientific interest, to the end that the health, happiness, recreational opportunities and wholesome enjoyment of the life of the people may be further encouraged."

Prior to the authorization of the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation, there existed in the state areas designated "scenic and recreational," usually parks and campgrounds. Since 1907 these areas had been administered by the State Land Board. In 1947, state parks were transferred to the Highway Department, and responsibility grew with the addition of a number of roadside areas, where motorists on the freeway might pull off for a night's rest. In 1949 control of the parks system was transferred to the State Land Board. A Parks Division was created within the Land Board in 1953. John W. Emmert, a retired former superintendent of Glacier National Park, took charge of the Idaho program in April 1958. This form of administration continued until 1959 when Emmert was replaced with three regional directors. Since 1965, the Department has been governed by a six-person bipartisan board, each member representing a different geographic area of the state.

Since it's inception the State Parks system has grown to include over 25 park and recreation areas. It is of interest to note that despite the vast wildernesses and high percentage of federal lands in Idaho, the state does not have a single national park within its boundaries. The National Park Service does however administer several national monuments and reserves in Idaho.

On August 25, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson signed the act creating the National Park Service, a new federal bureau in the Department of the Interior responsible for protecting the 40 national parks and monuments then in existence and those yet to be established.

This "Organic Act" of August 25, 1916, states that "the Service thus established shall promote and regulate the use of Federal areas known as national parks, monuments and reservations . . . by such means and measures as conform to the fundamental purpose of the said parks, monuments and reservations, which purpose is to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations."

The National Park System of the United States comprises 378 areas covering more than 83 million acres in 49 States, the District of Columbia, American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, Saipan, and the Virgin Islands. These areas are of such national significance as to justify special recognition and protection in accordance with various acts of Congress.

By Act of March 1, 1872, Congress established Yellowstone National Park in the Territories of Montana and Wyoming "as a public park or pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people" and placed it "under exclusive control of the Secretary of the Interior." The founding of Yellowstone National Park began a worldwide national park movement. Today more than 100 nations contain some 1,200 national parks or equivalent preserves.

In the years following the establishment of Yellowstone, the United States authorized additional national parks and monuments, most of them carved from the federal lands of the West. These, also, were administered by the Department of the Interior, while other monuments and natural and historical areas were administered as separate units by the War Department and the Forest Service of the Department of Agriculture. No single agency provided unified management of the varied federal parklands.

An Executive Order in 1933 transferred 63 national monuments and military sites from the Forest Service and the War Department to the National Park Service. This action was a major step in the development of today's truly national system of parks - a system that includes areas of historical as well as scenic and scientific importance.

Congress declared in the General Authorities Act of 1970 "that the National Park System, which began with the establishment of Yellowstone National Park in 1872, has since grown to include superlative natural, historic, and recreation areas in every region ... and that it is the purpose of this Act to include all such areas in the System...."

Additions to the National Park System are now generally made through acts of Congress, and national parks can be created only through such acts. But the President has authority, under the Antiquities Act of 1906, to proclaim national monuments on lands already under federal jurisdiction. The Secretary of the Interior is usually asked by Congress for recommendations on proposed additions to the System. The Secretary is counseled by the National Park System Advisory Board, composed of private citizens, which advises on possible additions to the System and policies for its

Parks & Monuments

The Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation has historically utilized its enabling legislation (Idaho Code 67-4219) as its mission statement: "It is the intent of the legislature that the department of parks and recreation shall formulate and put into execution a long range, comprehensive plan and program for the acquisition, planning, protection, operation, maintenance, development and wise use of areas of scenic beauty, recreational utility, historic, archaeological or scientific interest, to the end that the health, happiness, recreational opportunities and wholesome enjoyment of the life of the people may be further encouraged."

Prior to the authorization of the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation, there existed in the state areas designated "scenic and recreational," usually parks and campgrounds. Since 1907 these areas had been administered by the State Land Board. In 1947, state parks were transferred to the Highway Department, and responsibility grew with the addition of a number of roadside areas, where motorists on the freeway might pull off for a night's rest. In 1949 control of the parks system was transferred to the State Land Board. A Parks Division was created within the Land Board in 1953. John W. Emmert, a retired former superintendent of Glacier National Park, took charge of the Idaho program in April 1958. This form of administration continued until 1959 when Emmert was replaced with three regional directors. Since 1965, the Department has been governed by a six-person bipartisan board, each member representing a different geographic area of the state.

Since it's inception the State Parks system has grown to include over 25 park and recreation areas. It is of interest to note that despite the vast wildernesses and high percentage of federal lands in Idaho, the state does not have a single national park within its boundaries. The National Park Service does however administer several national monuments and reserves in Idaho.

On August 25, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson signed the act creating the National Park Service, a new federal bureau in the Department of the Interior responsible for protecting the 40 national parks and monuments then in existence and those yet to be established.

This "Organic Act" of August 25, 1916, states that "the Service thus established shall promote and regulate the use of Federal areas known as national parks, monuments and reservations . . . by such means and measures as conform to the fundamental purpose of the said parks, monuments and reservations, which purpose is to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations."

The National Park System of the United States comprises 378 areas covering more than 83 million acres in 49 States, the District of Columbia, American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, Saipan, and the Virgin Islands. These areas are of such national significance as to justify special recognition and protection in accordance with various acts of Congress.

By Act of March 1, 1872, Congress established Yellowstone National Park in the Territories of Montana and Wyoming "as a public park or pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people" and placed it "under exclusive control of the Secretary of the Interior." The founding of Yellowstone National Park began a worldwide national park movement. Today more than 100 nations contain some 1,200 national parks or equivalent preserves.

In the years following the establishment of Yellowstone, the United States authorized additional national parks and monuments, most of them carved from the federal lands of the West. These, also, were administered by the Department of the Interior, while other monuments and natural and historical areas were administered as separate units by the War Department and the Forest Service of the Department of Agriculture. No single agency provided unified management of the varied federal parklands.

An Executive Order in 1933 transferred 63 national monuments and military sites from the Forest Service and the War Department to the National Park Service. This action was a major step in the development of today's truly national system of parks - a system that includes areas of historical as well as scenic and scientific importance.

Congress declared in the General Authorities Act of 1970 "that the National Park System, which began with the establishment of Yellowstone National Park in 1872, has since grown to include superlative natural, historic, and recreation areas in every region ... and that it is the purpose of this Act to include all such areas in the System...."

Additions to the National Park System are now generally made through acts of Congress, and national parks can be created only through such acts. But the President has authority, under the Antiquities Act of 1906, to proclaim national monuments on lands already under federal jurisdiction. The Secretary of the Interior is usually asked by Congress for recommendations on proposed additions to the System. The Secretary is counseled by the National Park System Advisory Board, composed of private citizens, which advises on possible additions to the System and policies for its management.

|

|

Established in 1970

When wind looses its velocity and its ability to transport the sand it has carried from the surface, it deposits it on the ground. Sand deposits tend to assume recognizable shapes. Wind forms sand grains into mounds and ridges called dunes, ranging from a few feet to hundreds of feet in height. Some dunes migrate slowly in the direction of the wind. A sand dune acts as a barrier to the wind by creating a wind shadow. This disruption of the flow of air may cause the continued deposition of sand. A cross section or profile of a dune in the direction of blowing wind shows a gentle slope facing the wind and a steep slope to the leeward. A wind shadow exists in front of the leeward slope which causes the wind velocity to decrease. The wind blows the sand grains up the gentle slope and deposits them on the steep leeward slope.

History

The Bruneau Sand Dunes State Park, established in 1970, is located about 8 miles east-northeast of Bruneau and about 18 miles south of Mountain Home. The dunes at Bruneau Dunes State Park are unique in the Western Hemisphere. Other dunes in the Americas form at the edges of natural basins; these form near the center.

The combination of 1) a source of sand; 2) a relatively constant wind activity; and 3) a natural trap have caused sand to collect in this semicircular basin for over 20,000 years. Geologists believe the dunes seen today may have started with sands from the Bonneville Flood about 15,000 years ago.

Unlike most dunes, these do not drift far. The prevailing winds blow from the southeast 28 percent of the time and from the northwest 32 percent of the time, keeping the dunes fairly stable.

Although there are many small dunes in the area, two prominent dunes cover approximately 600 acres. These two imposing dunes are striking, particularly because they dwarf most of the nearby land features. The westernmost dune is reported to be the largest single-structured sand dune in North America with a peak 470 feet above the level of the lakes.

Desert Habitat

The park contains lake, marsh, desert, prairie and dune habitats. Since most desert wildlife is nocturnal, early morning and late evening are the best times for spotting the park's inhabitants. However, a sharp eye often is rewarded with a daytime glimpse of lizards and rabbits, or raptors such as owls, hawks, and eagles. There is no hunting in the park except with cameras and binoculars.

The colors of a desert sunset are found again in the early-morning blossoms of the sunflower and desert lily. A coyote may howl at the same moon you watch reflected in the still lakes. A cool shore breeze refreshes after a climb on the warm sands, and the lakes teem with waterfowl.

The Lakes

The small lakes at the foot of the dunes provide an excellent bass and bluegill fishery, Sport fishing from non motorized boats, canoes, rubber rafts, and float tubes is a popular activity.

Camping

Bruneau Dunes has one of the longest camping seasons in Idaho's system. Campers often start coming in March and continue to enjoy the park's warm weather late into the fall. Shade trees and shelters are abundant in the campground.

Environmental Education

The environmental-education center features displays of area wildlife and natural history.

The Eagle Cove Interpretive Program Area can be reserved for schools or other groups of 30-40 persons. Contact the park for details.

|

|

|

|

Established in 1988

The "Silent City of Rocks" covers a 10-square mile area in Cassia County, approximately 4 miles from the Idaho-Utah border. It is situated 15 miles southeast of Oakley and about 4 miles west of Almo. You can reach the City of Rocks by traveling through Oakley on the west or through Almo on the east; both routes involve travel on graded gravel roads.

The City of Rocks has been designated as a natural and historic national landmark and is under study by the Bureau of Land Management and the National Park Service for inclusion in the park system. The major obstacle to establishing better protection and management of the area is the mixed ownership. The Forest Service administers 1,120 acres; the Bureau of Land Management administers 1,040 acres, 640 acres is owned by the State of Idaho; and the remaining 4,000 acres is in private ownership.

History

Shoshone-Bannock tribes hunted the buffalo that once roamed in the City of Rocks area and gathered the nuts of the pinyon pine trees. The return of horses to the Americas in the 16th century and swelling European immigration disrupted the Shoshone-Bannock homelands and way of life. In 1826, Peter Skene Ogden and his Snake River brigade of beaver trappers were the first non-Native Americans to note the City of Rocks. Having few beaver, the area was ignored until 1843, when growing summer streams of wagons began flowing through the area. The Shobans grew to resent the intruders but could do little to stop them.

The junction of the California and Salt Lake-California connection trails is located 1.5 miles south of Twin Sisters. The California Trail, which passes through the City of Rocks, was established in 1843 when Joseph Walker led a wagon train off of the Oregon Trail at Raft River 50 miles to the northeast, through Almo, then through the City of Rocks and on to California.

Most emigrants on the California Trail saw no Native Americans, but some of their journals record smoke signals rising from high hills and the surrounding mountains. Immigrants were fascinated by the City of Rocks and those who maintained diaries recorded their impressions. Typical is the following description given by a Mr. Lord on August 17,1849: " numerous artificial hydrants forming irregular pointed cones. Nearby they display all manner of fantastic shapes. Some of them are several hundred feet high and split from pinnacle to base by numerous perpendicular cracks or fissures. Some are domelike and the cracks run at different angles breaking up the large masses into huge blocks many of which hang tottering on their lofty, pointed beds ... I have not time to write the hundredth part of the marvels of the valley or rocks . . ." Some of those pioneers left their names in axle grease on rocks in the Reserve. Many can still be seen today.

Early emigrant groups were guided by experienced mountain men such as Joseph B. Chiles. Later wagon parties followed the trails themselves, perhaps with the help of diary accounts of previous emigrants. The City of Rocks marked progress west for the emigrants and, for their loaded wagons, a mountain passage over nearby Granite Pass. By 1846, emigrants headed for Oregon's Willamette Valley also used this route as part of the Applegate Trail. In 1848 the Mormon Battalion opened the trail from Granite Pass via emigrant Canyon to Salt Lake. In 1852, some 52,000 people passed through the City of Rocks on their way to the California goldfields.

When the trails opened in the 1840's, Granite Pass was in Mexico and less than a mile from Oregon Territory, which included the City of Rocks. After 1850 the area became part of Utah Territory, and in 1872 the Idaho-Utah boundary survey placed the City of Rocks in Idaho Territory. With completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, the overland wagon routes began to pass into history. However, wagons saw continued use on regional supply routes that spread out from the railroad lines.

John Halley's stage route connected the railroad at Kelton, Utah with Idaho's mining hub of Boise and supplied the early economic developmnt of Idaho, which won statehood in 1890. The Kelton stage route passed through the City of Rocks, with a stage station set up near the junction of the old California Trail and the Salt Lake Alternate. Settlers began to homestead the City of Rocks area in the late 1800s. Dryland farming declined during the drought years of the 1920s and 30s, but ranching survived. Livestock grazing began with early wagon use of the area in the mid-1800s and continues today.

Geologic Setting

The Silent City of Rocks is situated in the Cassia Batholith. This small batholith covers more than 60 square miles in the southern part of the Albion Range. The batholith was at one time covered by a thin shell of Precambrian quartzite. Once the upper shell of protective quartzite was eroded away, the granite below eroded down at a more rapid rate. Consequently the City of Rocks is situated in a basin. Within the City of Rocks, more than 5,000 feet of granitic rock are exposed from the top of Cache Peak to the bottom of the basin.

More like mother and daughter than siblings, the composition of the well-known Twin Sisters helps to illustrate how the City of Rocks came to be. The darker sister is made of rock that geologists call the Green River Complex. It is 2.5 billion years old and is some of the oldest rock in the lower 48 states. The lighter sister is made of rock in a far younger formation that geologists call the Almo Pluton. At 25 million years old, it is a relative newborn.

Both formations began as molten matter in the Earth's crust. Eventually the Almo Pluton was thrust up through the Green River Complex while both formations still lay beneath the Earth's surface and other layers of rock. As time passed, the overlying rocks and the formations beneath them cracked. Along the cracks and fissures erosion took place more rapidly and exposed the rocks of the Almo Pluton and Green River Complex.

Jointing

Jointing is well developed in some parts of the batholith and is an important structural control in establishing the basic forms in the City of Rocks. Spacing of the joints varies widely. There are three intersecting joint sets: a northwest trend, a northeast trend, and a horizontal trend. Jointing controls the arrangement of outcrops. Joints facilitate the weathering processes by providing a plumbing system for solutions to migrate into the outcrops to cause the alteration and disintegration of surface layers of granite. These large fracture channels for fluids make it possible for blocks to separate and form tall, isolated monoliths such as spires and turrets.

Rock Types

The Cassia Batholith contains rock ranging from granite to granodiorite. The inner core occupied by the City of Rocks tends to be granodiorite; whereas granite is more common for the outer area. A gneissic texture is characteristic of the outer zone.

The Almo Pluton

The granite in the City of Rocks is part of the Almo pluton. Armstrong (1976) has determined that this epizonal (shallow) pluton is 28.3 million years old, much younger than most of the granitic rock in Idaho. The shallow emplacement of the pluton is indicated by its lack of foliation at the margins and the discordant contacts it makes with the surrounding older quartzite.

Pegmatites

Scattered pegmatite dikes, which have the composition and texture of coarse-grained granite, may be observed throughout the Cassia Batholith. Pegmatites range from thin seams to lenticular bodies up to 50 feet across and several hundred feet long. One exceptionally large pegmatite crops out in the City of Rocks. This pegmatite may be one of the largest to be found in Idaho with exposed dimensions of 200 to 300 feet wide and 400 to 500 feet long. Large masses of orthoclase feldspar, quartz and muscovite are well exposed over two rounded knolls that make up the pegmatite. Some of the masses of quartz and feldspar are tens of feet in diameter. Masses of muscovite display radiating crystals. Smoky quartz and miarolitic cavities are common. Numerous small workings over this large pegmatite show evidence of past interest and activity.

Weathering

Although jointing controls the general form of outcrops in the City of Rocks, weathering is the agent responsible for creating the bizarre and fantastic shapes that characterize the area. On the surface of the outcrops the weathering occurs by granular disintegration. In other words one layer of crystals after another is successively removed from the surface, This leaves the newly exposed surface in a smooth rounded condition with no sharp or ragged edges or corners. The detrital material weathers from the granite and is carried by wind and water to low areas among the prominent forms. This process has already removed some of the layers of rock bearing 150-year-old signatures left by the pioneers.

Wildlife

Part of Idaho's Minidoka Bird Refuge, the City of Rocks is home to eagles, falcons, vultures, hawks, hummingbirds, jays, sparrows, doves, and the state bird, the mountain bluebird. Among the mammals that live within the park are elk, mule deer, mountain lions, coyotes, badgers, bobcats, porcupines, ground squirrels, and bats. Reptiles such as the sand lizard, watersnake, blowsnake, rubber boa, and the park's only poisonous snake, the rattlesnake (found only at lower elevations), also live within the City of Rocks. All plants and animals are protected by law and should not be disturbed.

Vegetation

The range of elevations within the compact area of the Reserve combines with other factors to create varied patterns of vegetation and wildlife habitat. At high elevations the forests are of lodgepole pine, limber pine, and Douglas fir. Middle elevation forests are of quaking aspen, mountain mahogany, and cottonwood. Sagebrush, pinyon pines, and juniper dominate lower elevations. The Reserve boasts Idaho's tallest pinyon pines, at more than 55 feet. The nuts of the trees provide important proteins and fats for wildlife. In addition to the trees, spring and summer displays of wildflowers can be spectacular. Over 450 plant species have been recorded at the City of Rocks.

|

|

||

|

||

Established in 1924

Craters of the Moon National Monument, established in 1924, is the result of basaltic volcanic activity between 15,000 and 2,100 years ago.

Topography

Craters of the Moon lies at the north edge of the eastern Snake River Plain. There are two distinct landforms in the monument: the foothills of the Pioneer Mountains in the north give way to the low relief of the lava flows in the rest of the monument. The monument's highest elevation is in the Pioneer Mountains, 7,729 feet above sea level. The lowest elevation is about 5,330 feet located in the southeast corner of the monument. Elevations gradually decrease from north to south. Within the lava flows, cinder cones provide the greatest vertical relief. The highest cinder cone is Big Cinder Butte which stands more than 700 feet above the surrounding plain. Nineteen other cinder cones are at least 100 feet high. The Great Rift is apparent from the linear alignment of the cinder cone.

Volcanic Features

The primary resource value of Craters of the Moon is the great diversity of basaltic features in a small area. Almost all the features of basaltic volcanism are visible at the monument.

Much of the volcanism of the Snake River Plain was confined to volcanic rift zones. A volcanic rift zone is a concentration of volcanic landforms and structures along a linear zone of cracks in the earth's crust. The Great Rift volcanic rift zone is a zone of cracks running approximately northwest to southeast across almost the entire eastern part of the Snake River Plain. The entire Great Rift is 62 miles long.

The Great Rift is an example of basaltic fissure eruption. This type of volcanic activity is characterized by extrusion of lavas from fissures or vents that is relatively quiet in comparison with highly explosive eruptions such as the 1980 Mount Saint Helens eruption.

Where the Great Rift intersects the earth's surface, there is an array of cinder cones, lava cones, eruptive fissures, fresh-appearing lava flows, noneruptive fissures, and shield volcanoes.

Of the more than 60 lava flows of the Craters of the Moon lava field, 20 have been dated: their ages were found to range from about 15,000 years before present to about 2,100 years before present. The flows were laid down in eight distinct eruptive periods that recurred on an average of every 2,000 years. On the basis of recent eruptive history, the Craters rift set is due for another eruption within the next thousand years, perhaps as soon as within 200 years.

Brief Chronology of Geologic Events at Craters of the Moon

1. Around 8 million years ago the Yellowstone Hot Spot was beneath Craters of the Moon (the caldera to the west is 10 million and the one to the east is 6 million). A time of violent rhyolitic eruptions.

2. Between 6 million and 15,000 years ago basaltic eruptions produce about a 4,000-ft. thickness of basalt flows (data from east of park).

3. Between 15,000 and 2,000 years ago the present day surface of the Craters of the Moon Lava Field forms during 8 major eruptive periods. During this time the Craters of the Moon Lava Field grows to cover 618 square miles.

4. Today the monument preserves and protects 83 square miles of the lava field for present and future generations to enjoy and learn from.

The Hot Spot

One explanation for the existence of the Snake River Plain and the Craters of the Moon lava field is called the mantle plume theory. This theory states that beneath the crust of the Snake River Plain lies a "hot spot" or localized heat source. Periodically, this hot spot consists of a "plume" of molten rock (magma) which rises buoyantly to the surface of the earth. The hot spot does not move but rather remains in a fixed position. What does move is the crust of the earth; as the North American plate slides southwestward over the hot spot. As the plate moves over the hot spot volcanic eruptions occur creating a string of volcanic acitvity on the surface.

Initially these eruptions are very violent and produce a lava known as rhyolite. Huge calderas of up to 30 miles in diameter are formed when these devastating eruptions take place. Later a more fluid lava known as basalt flows onto the surface and covers the rhyolitic flows. Yellowstone National Park, the area where the hot spot is believed to be located at this time, is the place where catastrophic rhyolitic eruptions last occurred 600,000 years ago. Craters of the Moon represents the second stage of the eruptions where fluid basaltic lava covered the landscape as recently as 2,000 years ago.

Geologic Description

The Craters of the Moon (COM) Lava Field is made up of about 60 lava flows and 25 cones. It is the largest and most complex of the late Pleistocene and Holocene basaltic lava fields of the Eastern Snake River Plain (ESRP). The lava flows here exhibit a wide range of chemical compositions. In the last 15,000 years there have been 8 major eruptive periods at COM. In contrast, most of the other lava fields in the ESRP represent just single eruptions, have about the same composition (olivine tholeiites, i.e. silica over-saturated basalt), and were widely scattered in space and time.

The COM lava field formed from magma (molten rock below the surface of the earth), which came up along the Great Rift. The Great Rift is a system of crustal fractures. It extends from the base of the Pioneer Mountains near the visitor center off to the SE for 62 miles. COM lava field is the northern most of 3 lava fields found along the Great Rift. The Great Rift and other volcanic rifts on the ESRP are generally parallel to but not collinear with Basin and Range faults north and south of the plain.

When magma comes to the surface along a segment of a rift, it often begins by producing a curtain of fire, a line of low eruptions. As portions of the segment become clogged the fountains become higher. If magma comes to the surface highly charged with gas it is like taking the cap off of a bottle of pop that has been shaken-- it sprays high in the air. The fire fountains that produced many of the COM cinder cones were probably over a 1,000-ft. high. Big Cinder Butte, the tallest cinder cone in COM, is over 700-ft. high. The highly gas-charged molten rock cools and solidifies during flight and rains down to form the cinder cones. If you look at cinders you will see that they are laced with gas holes and resemble a sponge or piece of Swiss cheese; all the gas holes make cinders very light in weight.

Molten rock on the surface it is called lava. Of the 60 lava flows visible on the surface today, 20 have been dated. The oldest is about 15,000 years old and the youngest about 2,000. The lava flows at COM have similar parent (olivine tholeiitic) magma to the rest of the plain, but are fractionated and exhibit chemical characteristics of crustal contamination. Some lava flows had a smooth, ropy, or billowy surface—pahoehoe lava. Others were very dense and had a surface of angular blocks—block lava, while still others had a rough, jagged, or clinkery surface—aa lava. There are also 3 special kinds of pahoehoe that can be seen in the COM lava field: 1) slab pahoehoe, also known as semihoe, which is made up of jumbled plates or slabs of broken pahoehoe crust, 2) shelly pahoehoe, which forms from gas-charged lava and has small open tubes, blisters, and thin crusts, and 3) spiny pahoehoe, which was very thick and pasty and a transition phase to aa, has stretched elongated gas bubbles on the surface that form spines.

Most of the COM lava flows are pahoehoe and were fed through tubes and tube systems, though there are some sheet flows. In COM structures representing both inflation and deflation of the lava surface can be seen along with hot and cold collapses of the roofs of lava tubes. Inside lava tubes you can see lava stalactites, remelt features, and lava curbs. In other places lava flows formed ponds, built levees, and produced lava cascades. Some lava flows produced small mounds (tumuli) or elongate ridges (pressure ridges) on their crusts.

Some vents along the rift ejected very fluid particles (spatter) that accumulated to form steep sided spatter cones. Along eruptive fissures where a whole segment was erupting, spatter accumulated to produces low ridges called spatter ramparts. Similar in appearance to spatter cones are hornitos, also known as rootless vents. They formed from spatter that was ejected from holes in the crust of a lava tube instead of directly from a feeding fissure. COM also has rimless collapses known as sinks or pit craters. During some eruptions pieces of crater walls were carried off like icebergs by lava flows. These wall chunks are known as rafted blocks, the monoliths across from the visitor center are examples.

Monument History

The explorers, pioneers, miners, and ranchers, who traveled this area from the 1850s through the early part of this century, could find nothing to love about it. The parched and inhospitable lava beds were only an obstacle to get past as quickly as possible. All of that changed in 1918 when Robert W. Limbert, one of Idaho's most tireless and flamboyant promoters, began to explore Craters of the Moon. His curiosity piqued by stories of grizzly bears roaming the mysterious lava beds, he made two short trips into the area.

In the Spring of 1920 he was ready for a more daring undertaking. Accompanied by W.L. Cole of Boise, he completed a 17 day, 80 mile odyssey through the lava wilderness. They carried blankets, cooking gear, camera and tripod, binoculars, a compass, guns, and two weeks of dried food - 55 pounds of equipment each! They also brought along a camp dog, a decision they were to regret. After three days of travel over the rough lava, the dog's feet were raw and bleeding. For the remainder of the trip, Limbert and Cole had to carry the dog or wait for him to pick his way across the rock.

They crossed 28 miles of jagged aa flows the first three days. Sleeping at night was almost impossible, for they could not find a level place to lie down. To locate scattered waterholes, they followed old Indian or mountain sheep trails, or watched for places where groups of birds dropped from the sky to quench their thirst.

Throughout the trip Limbert photographed the landscape. He also gave colorful names to many features: Vermillion Canyon, Trench Mortar Flat, Echo Crater, Yellowjacket Water Hole, Amphitheater Cave, and the Bridge of Tears.

Limbert continued to explore the region following this journey. In 1921 he led 10 scientists and civic leaders into the lava fields and argued for protection of the area's volcanic features. During the trip he made over 200 still photographs and 4,000 feet of motion picture film.

Limber vividly described his experiences in a series of striking photo essays in newspapers and magazines. The most prominent was a 1924 National Geographic article entitled "Among the 'Craters of the Moon'." He wrote, "No more fitting tribute to the volcanic forces which built the great Snake River Valley could be paid than to make this region into a National Park." Limbert also sent President Calvin Coolidge a scrapbook with pictures and narration describing his trips along the Great Rift. Within two months after the article appeared, Coolidge issued a proclamation establishing Craters of the Moon National Monument. About 1,500 people traveled over the gravel and cinder roads to attend the dedication ceremony on June 15, 1924.

Limbert was the first person to recognize the potential of Craters of Moon to fascinate and delight visitors. He said, "Although almost totally unknown at present, this section is destined some day to attract tourists from all America, for its lava flows are as interesting as those of Vesuvius, Mauna Loa, or Kilauea." Although this prediction did not prove true in his lifetime, today more than 200,000 people visit Craters of the Moon National Monument each year.

Habitats

The barren, harsh lava flows of the monument often give the viewer the impression that this is a lifeless landscape. Even though animal populations may be relatively low on the lava itself, there are numerous hospitable habitats available here as well. Four of the most common habitats are:

1. Lava Flows

2. Cinder Areas

3. Riparian/Mountain

4. Kipukas

Older flows and cinder fields support a variety of different plant communities ranging from wildflower gardens, to sagebrush steppes, to dense forests. The different characteristics of the lava deposited here also provide varied environments of bare rock, deep cracks, jagged piles, cinder flats, and underground caves that support an equally varied group of wildlife species. The periodic eruption of lava created a mosaic of plant communities, all at different stages of succession with widely different plant and wildlife species.

Vegetation and Wildlife

Twenty-six distinct vegetation types have been described within Craters of the Moon (Day, 1985).

This unique mixture of habitats and differing vegetation supports a very diverse population of animals. A total of nearly 168 bird, 46 mammal, 8 reptiles, and 2 amphibian species have been reported in Crater of the Moon. Five of the animal species — grizzly bear, gray wolf, bison, porcupine, and bighorn sheep — are known to have been eliminated from the monument. For the most part, the animals found at the monument are those most common to the sagebrush steppe habitat of the intermountain west. Some of the common species seen at the Monument include:

1. Fox

2. Marmot

3. Mule Deer

In addition, three subspecies of unique small mammals endemic to the Snake River Plain were first identified in Craters of the Moon. A subspecies of the Great Basin pocket mouse was first taken from Echo Crater, as was the first specimen of a race of the pika. As might be expected for mammals that live on lava flows, both races are characterized by darker fur than other races of the species. The first specimen of a subspecies of the yellow-pine chipmunk came from Grassy Cone.

![]()

|

Terms & Phrases

|

Established in 1988

Introduction

There are many fossil sites located in Idaho. One of the most important of these is the Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument - the location of the "Hagerman Horse" fossils (Equus simplicidens) - Idaho's state fossil.

Hagerman Horse Bones

Hagerman is located in south-central Idaho on the Snake River. The beautiful Hagerman Valley was formed from the Bonneville flood, which swept through the Snake River Canyon approximately 14,500 years ago. Evidence of this flood can be found on the valley floor in the form of basalt boulders which were left by the receding flood water.

Melon gravels deposited

by the Bonneville Flood.

The Fossil Beds are located across the river to the southwest from the town in a series of steep bluffs formed by the Snake River cutting through the Glenns Ferry and Tuana formations. Erosion of the bluffs over time has revealed a spectacular view into Idaho's geologic past.

Sedimentary outcrops.

Elmer Cook, a cattle rancher living in Hagerman, Idaho, discovered some fossil bones on what is now monument land in 1928. He showed them to Dr. H.T. Stearns of the U.S. Geological Survey who then passed them on to Dr. J. W. Gidley at the Smithsonian Institution. Identified as bones belonging to an extinct horse, the area where the fossils were discovered was excavated and three tons of specimens were sent back to the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.

Of all the fossils uncovered, the most important find was the large volume of a species of extinct horse known as Equus simplicidens, and named the Hagerman horse.

Excavation continued into the early 1930's. The quarry floor grew to 5,000 square feet with a backwall 45 feet high. Ultimately five nearly complete skeletons, more than 100 skulls, and forty-eight lower jaws as well as numerous isolated bones were found. Finding such a large deposit of an animal in one location is a rare occurrence. An early explanation for the deposit was that the quarry area was once a watering hole where the bones of the Hagerman horses accumulated as injured, old, and ill animals, drawn to water, died there. It is now known that an entire herd of these animals probably drowned attempting to ford a flooded river and were swept away in the current. Their bodies were then quickly buried in the soft sand beneath the water.

The National Monument was established in 1988 to preserve the important finds. The Oregon Trail crosses the southern portion of Hagerman Fossil Beds. The monument is one of only 3 units in the national park system that contains parts of the Oregon National Historic Trail. In addition, many artifacts have been recovered that indicate the presence of Native Americans in the area.

Geology

Hagerman Fossil Beds are located on the eastern edge of the Western Snake River Plain. The general geology of the monument consists mainly of sediments of the Glenns Ferry and Tuana Formations of the Idaho Group which lie unconformably on siliceous Idavada volcanics. These sediments inter-bedded with an occasional basalt flow, silicic volcanic ash and basaltic pyroclastic deposits, range in age from 2.5 - 3.5 ma and represent deposition within lake, stream and flood plain environments. These unconsolidated sediments that outcrop at Hagerman have yielded a remarkable amount of fossils.

|

Established in 1967

Gate of Death and Devil's Gate were names given to this area during the Oregon Trail period. These names referred to a narrow break in the rocks through which the trail passed. Emigrants apparently feared that Indians might be waiting in ambush.

Diaries record a series of skirmishes between the Shoshone Indians and emigrants on August 9 and 10, 1862. Ten emigrants died in the fight, which involved five wagon trains.

The skirmishes took place east of the park and not at Devil's Gate as commonly believed. Some confrontations may have occurred there, but they remain unverified.

State Park

The Massacre Rocks State Park was created to preserve the geology, ecology and historical geography of this segment of the Snake River Plain.

Oregon Trail pioneers used the Register Rock area as a "rest stop" for years. Many emigrant names are inscribed on the large rock, which is now protected by a weather shelter. A scenic picnic area surrounds the rock, creating a desert oasis for the modern traveler.

Oregon Trail remnants are most easily seen from highway rest areas in either end of the park. Other settlers artifacts can also be found.

Geology

The park is rich in geological history. Volcanic evidence is everywhere. The Devil's Gate Pass is all that remains of an extinct volcano. Towering cliffs of basalt provide

fantastical formations throughout the park.

The prehistoric Bonneville Flood also shaped the landscape of the area, rolling and polishing the huge boulders found throughout the park. The flood was caused when eroding waters broke through Red Rock Pass near the Idaho/Utah border.

Lake Bonneville, which covered much of what is today the state of Utah, surged through the pass and along the channel of the Snake River in a few short months. For a time, the flow was four times that of the Amazon River. It was the second largest flood in the geologic history of the world.

Plant & Animals

Massacre Rocks State Park is a favorite for bird watchers. Over 200 species of birds have been sighted in the park. Canada geese, grebes, bald eagles, pelicans, and blue herons are often seen.

Mammals include the cottontail, jack rabbit coyote, muskrat, and beaver.

The desert environment produces about 300 species of plants in the park. The most common are sagebrush Utah juniper, and rabbit brush.

National Forests

Introduction

Idaho is lucky to have so many beautiful forests. Almost everyone loves the mountains and enjoys the trees and animals. Though we enjoy the pleasures of the forests, the trees are valuable for other reasons as well. The forests are most important because they are part of our watershed. They help store snow and water, and control the amount of water in our streams and rivers. The trees shade the snow and make it melt more slowly. Without shade, the snow would melt too quickly. The tree roots hold the soil in place. Without roots, the soil would wash away. The soft, spongy forest floor also stores some of the water and lets it trickle clean and clear into the streams. Without the trees, the water would run down the streams and rivers in a big, muddy rush. There would be a huge, muddy spring flood, then no water later in the summer.

Idaho forests are important for another reason. They provide jobs and many of the things we use every day. Trees are used to make our houses, furniture, railroad ties, wooden boxes, wooden matches, rayon, and paper - among other things.

Native trees of the Panhandle and mountains of Idaho include aspens and needleleaf trees. These trees grow straight and tall. They are also known as evergreens. This means that these trees are green all year long and never lose all their leaves like broadleaf trees do. Several important kinds of needleleaf trees make up Idaho's forests. The most valuable is the western white pine. Idaho has the largest stand of white pine forest left in the United States. Its clear, straight grain makes it excellent for lumber and wooden matches. Next in value are the ponderosa or western yellow pine and the Douglas fir . These are excellent for lumber and timbers. Another interesting and valuable Idaho tree is the western red cedar. It is used for furniture, fence posts, telephone poles, and other uses. The largest living tree in Idaho is the red cedar growing in Land Board State Park near Elk River. It is sixteen feet through the trunk, and more than 150 feet tall. It is thought to be between 2,000 and 3,000 years old. This is nearly as old as the famous redwoods of California.

History

People have been using Idaho's trees for a long, long time. Indians used small trees to make poles for their tipis - particularly lodgepole pine. They made dugout canoes by cutting and burning out the inside of larger trees. Lewis and Clark made canoes this way near Orofino in 1805. They rode these canoes down the Snake and Columbia rivers to the Pacific Ocean.

Henry Spalding built Idaho's first sawmill in 1840 on the Clearwater River. The mill sawed logs into boards, and ground grain into flour. It was powered by a water wheel.

Trappers and early gold miners built cabins from logs.

The nicer buildings in the mining camps were made from boards cut with a two-man whipsaw. This saw was six or seven feet long, with very coarse teeth and a handle on each end. A log was laid out so one man could stand above the log, and another man could stand under it. The man under the log pulled the saw down and got sawdust in his eyes. The man above pulled the saw back up. The saw was pulled back and forth until the log was cut from end to end. It was slow work, and it took two cuts to make the first board. Heavy timbers sometimes had each side squared off with a whipsaw. More often the sides were squared by a man using an ax.

Small water-powered sawmills appeared in all parts of Idaho during territorial times. These small mills served the needs of the mining and farming towns. There was a never-ending demand for lumber. Government laws allowed people to use trees for home and farm use. A person could buy as much as 160 acres of forest land, but when those trees were gone, he was out of the lumbering business. Large lumber companies were not allowed to cut Idaho timber until 1892, when the laws were changed. Even the railroads could not cut Idaho's trees. When the railroads built their tracks across Idaho, they had to haul their wooden ties from as far away as the Black Hills of South Dakota.

During the 1800's, lumbermen thought only of cutting down all the big trees in the forest, then moving on to a new forest. They gave no thought to saving the younger trees for later harvests, or to planting young trees for future forests. After the lumbermen moved on, other people burned the stumps and trash. Much of the trash was crushed trees which were too small for lumber. The cleared land was then plowed for farming. Those forests were lost forever. The state of Maine lost its fine forests very early.

During the 1880's and 1890's, most of America's lumber was being cut in the Great Lakes states. By 1900, most of the good forests of Wisconsin, Michigan, and Minnesota were gone. Lumbermen were looking for new forests to cut. The forests of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana seemed ideal. After the Northern Pacific Railroad was built across Idaho's panhandle in 1880-1882, lumber was easy to ship. Idaho's white pine was a special prize which sold for high prices.

Lumbermen from the Great Lakes country began buying Idaho forest land in 1890. At least one company had a mill at Coeur d'Alene as early as 1890, though it was against the law until 1892. The lumbermen bought great amounts of Idaho timber land. They began building mills, and the lumbering business spread to most parts of Idaho, both north and south.

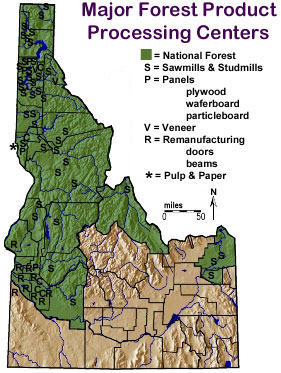

Forest Service

President Theodore Roosevelt loved the outdoors, and he worried that all of America's forests might be destroyed. While he was President from 1901 to 1909, he set aside 148 million acres of forest to be our national reserves. He then created the Forest Service to take care of the forest reserves. He chose Gifford Pinchot to be in charge of the Forest Service. Pinchot was a well-known conservationist. The forest reserves are now called national forests. Idaho has sixteen national forests, and they cover more than 20 million acres - more than any other state except Alaska. This is about two-fifths of all the land in Idaho. Idaho's national forests are the Bitterroot, Boise, Cache, Caribou, Challis, Clearwater, Coeur d'Alene, Kaniksu, Kootenai, Lolo, Nez Perce, Payette, Salmon, Sawtooth, St. Joe, and Targhee.

President Theodore Roosevelt loved the outdoors, and he worried that all of America's forests might be destroyed. While he was President from 1901 to 1909, he set aside 148 million acres of forest to be our national reserves. He then created the Forest Service to take care of the forest reserves. He chose Gifford Pinchot to be in charge of the Forest Service. Pinchot was a well-known conservationist. The forest reserves are now called national forests. Idaho has sixteen national forests, and they cover more than 20 million acres - more than any other state except Alaska. This is about two-fifths of all the land in Idaho. Idaho's national forests are the Bitterroot, Boise, Cache, Caribou, Challis, Clearwater, Coeur d'Alene, Kaniksu, Kootenai, Lolo, Nez Perce, Payette, Salmon, Sawtooth, St. Joe, and Targhee.

Before 1940, fires burned more trees than were harvested by the lumber companies. The worst fire in the history of North America was in northern Idaho and western Montana in 1910. Though it burned only two days, the Great Fire of 1910 destroyed 3 million acres of forest, making a burn 160 miles long and fifty miles wide. Four towns and many mines and mills were destroyed. More than 100 people died when they were trapped by the fast-moving flames. Elk City was saved by its women and children, but one part of Wallace burned to the ground. One-sixth of all the forest in northern Idaho was burned. Scars from this great fire could be seen along U. S. Highway 10 (the old Mullan Road) between Wallace and Missoula, Montana, for more than fifty years.

One good thing came from this terrible fire. It made more Americans want something done to save our forests. Congress had not been very interested in the Forest Service after Theodore Roosevelt left the White House in 1909. After the Great Fire, however, Congress saw the need to give the Forest Service more money. Since then, the Forest Service has grown, and today it does a fine job of protecting our forests.

The Forest Service is now well known for its fighting of forest fires. It has a system of forest roads, telephone lines, and lookouts. Airplanes also fly over the forests looking for fires. When a fire is spotted, everything possible is done to put it out before it gets bigger. Fire fighters (called smokejumpers) are rushed to the fire by airplane. Airplanes are used to dump water and chemicals on the fire. Forest fires are still a danger to our forests, and every citizen must do all he can to prevent them.

The Forest Service also protects the forests by fighting insect infestations and diseases which kills millions of trees every year.

Forestry Science

The science of logging - the cutting and hauling of logs - has grown with the rest of Idaho. Up-to-date power machinery has taken the place of the ax and two-man whipsaw for cutting down trees. One man with a small chain saw can do the work of several old-time lumber jacks. Logs are still being floated down Lake Coeur d'Alene to the mills, and trucks and trains still haul logs, which are loaded with cranes and other equipment. However, the exciting days of log drives down the Clearwater River from the mountains to Lewiston are only a memory. Dams have made that impossible. Today helicopters carry logs from steep hillsides and other places where there are no roads

The science of logging - the cutting and hauling of logs - has grown with the rest of Idaho. Up-to-date power machinery has taken the place of the ax and two-man whipsaw for cutting down trees. One man with a small chain saw can do the work of several old-time lumber jacks. Logs are still being floated down Lake Coeur d'Alene to the mills, and trucks and trains still haul logs, which are loaded with cranes and other equipment. However, the exciting days of log drives down the Clearwater River from the mountains to Lewiston are only a memory. Dams have made that impossible. Today helicopters carry logs from steep hillsides and other places where there are no roads

In the early days lumber companies cut large areas of timber without thinking of the damage to the land. All the trees in an area were cut and a large amount of the wood was lost because it was not the right size or type of wood.

In the 1920s and 1930s people began to understand that by cutting only mature trees, the forests could be saved for the future, and the timber companies could continue to make money. The lumber companies of today manage the forests very carefully. Some of the most beautiful and most successfully managed forests in Idaho are those run by the timber companies.

In the 1920s and 1930s people began to understand that by cutting only mature trees, the forests could be saved for the future, and the timber companies could continue to make money. The lumber companies of today manage the forests very carefully. Some of the most beautiful and most successfully managed forests in Idaho are those run by the timber companies.

The Forest Service has the job of making sure the national forests are put to the best use for all Americans, present and future. The Forest Service sells trees to lumber companies as they are needed, and makes sure the companies use good forest management. One kind of good management is called selective cutting. Only the large trees, or dead trees are cut. The loggers try to work carefully so they won't damage very many of the younger trees. Young trees are then planted to take the place of those cut. Planting young trees in the forest is called reforestation.

When the young trees grow large, the Forest Service will allow them to be cut, and more young ones will be planted to take their place. In this way, trees are harvested like a crop instead of being mined from the ground. This keeps the forests growing forever, and America will have both trees and lumber for as long as the forests keep growing.

Additional changes are being made in terms of road construction, trail building and the like. Such activities have slowed considerably and are conducted in a much more ecologically sound manner today than in the past.

Economics & Uses

Economics In the days of the mines, timbers to support the tunnels as well as boards and timbers for housing and places of business were needed. Local lumber companies provided each community with the wood products it needed.

In the days of the mines, timbers to support the tunnels as well as boards and timbers for housing and places of business were needed. Local lumber companies provided each community with the wood products it needed.