Idaho State University researchers use cockroaches to search for narcotics

May 2, 2019

POCATELLO – Idaho State University researchers, led by biological sciences master’s student Kayla Pavlick, are experimenting with cockroaches to see how well they can be trained to detect narcotics.

“We are training them to detect cocaine and Adderall XR (an amphetamine),” Pavlick said. “It is a really simple design, but it takes a long time. We are just rewarding them sugar water when we give them drugs.”

She said it’s possible in the future cockroaches could be used to complement canine units that search for drugs or the cockroaches could be used in environments where canines can’t be used, although this is out of the scope of her current research.

So far, Pavlick, working with biological sciences undergraduate student Walker Mink and biological sciences professor Dave Delehanty, has had encouraging results working with the cockroaches to find illegal drugs. They are working with “real American cockroaches,” scientific name Periplaneta americana.

“I am soaking little bits of filter paper in those solutions and presenting it to the cockroaches and paring that olfactory stimulus, that smell that they are getting, with a sucrose solution because they really love sugar,” said Pavlick, who is originally from Jackson, Mississippi.

“I am soaking little bits of filter paper in those solutions and presenting it to the cockroaches and paring that olfactory stimulus, that smell that they are getting, with a sucrose solution because they really love sugar,” said Pavlick, who is originally from Jackson, Mississippi.

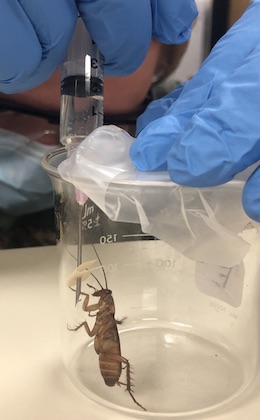

During the first stage of her experiment, the ISU researchers rewarded cockroaches with sugar water after the insects investigated a filter paper containing narcotics that was put in a beaker.

Then, the cockroaches were put in a testing chamber that Pavlick designed, that was separated into two sides. On one side of the chamber a cockroach would be released and on the other side there were four compartments, each with a petri dish, with only one of the petri dishes having a narcotic and the others loaded with vanilla. After lifting a barrier between the two sides, the cockroaches were tracked to which petri dish they would visit. They consistently chose the petri dish with drugs.

“They were very consistent,” Pavlick said.

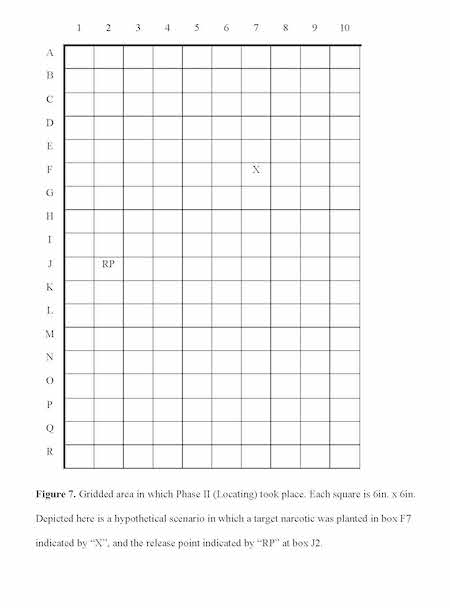

The second phase of the experiment was larger scale. The researchers used and 5-foot by 9-foot square enclosure and gridded it off, and then randomly planted the target substance drugs in different grids. They then released cockroaches into the larger grid and tracked how well the cockroaches went to the target substances. They tagged the cockroaches with metallic or infrared paint, mounted an infrared camera from the ceiling of the laboratory, and tracked where the cockroaches went.

Eight of the 10 cockroaches released successfully located the drug Adderall and seven of 10 cockroaches found the cocaine.

Eight of the 10 cockroaches released successfully located the drug Adderall and seven of 10 cockroaches found the cocaine.

“I think the experiment went really well,” Pavlick said. “This is likely the first time anything like this has been done with insects as far as a location task is concerned and on non-food borne odors, the narcotics. Even though they didn’t have a 100 percent success rate the results are still promising.”

The hardest part about pulling off the experiment was getting the drugs used with the cockroaches.

“The reason we couldn’t get anything done for so long is because obtaining narcotic drugs legally is quite the process,” she said. “It took some time getting the licensing from everybody we need and clearing it with the Office of Research so no one would get in trouble.”

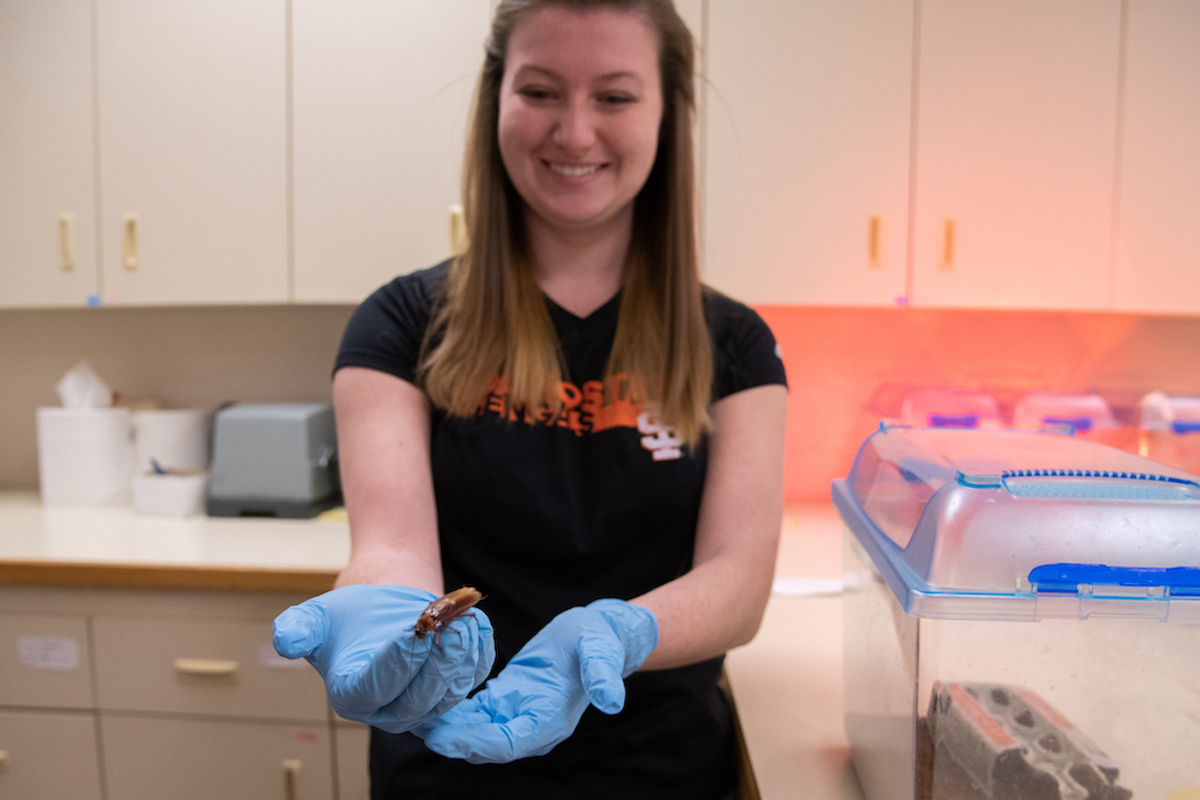

Working with cockroaches has helped the ISU students gain some unusual skills.

“There are certain skills you acquire that you think you will never acquire,” Pavlick said. “And one of those things is your reaction time, because these guys are so fast. They are incredibly fast.”

Pavlick said she is used to the insects crawling around on her when she is working with them.

“They just kind of tickle when they crawl on you,” she said. “When you first feel a cockroach on you your initial reaction is not to coddle it, and luckily with my undergraduate education I handled a lot of tarantulas and scorpions. They are not malicious in any way and they don’t bite. It’s funny, they actually develop personalities and Walker has named a couple of them.”

The cockroaches have a life span of up to 18 months and the researchers have worked with between 50 and 150 of them since the project began.

“Way down the line in the future, the way I see it playing out is that insects and cockroaches, specifically, could be used to complement current detection methods,” she said. “Canines are fantastic and they’ve been very useful for narcotic and explosive detection, but they do have limitations. One of them is their size – they can’t fit everywhere a roach can.”

Hypothetically, a canine detection unit could be employed to narrow down an area search and then insects could be used to exactly pinpoint the source. With current technology, it would even be possible to outfit cockroaches with tiny electronic GPS tracking device.

Hypothetically, a canine detection unit could be employed to narrow down an area search and then insects could be used to exactly pinpoint the source. With current technology, it would even be possible to outfit cockroaches with tiny electronic GPS tracking device.

“Somebody has already done that so now we just have to train the roaches successfully, so you could track them from afar using GPS technology,” she said.

She emphasized that cockroaches would never replace canines, but could potentially augment the use of them.

Pavlick, who will graduate this spring, successfully defended her master’s thesis, which was devoted to this project. She will pursue a Ph.D. program in biological sciences and plans to complete a scientific paper about the project and submit it to a journal.

Photo information:

Second Photo: Cockroach in beaker is being introduced to a narcotic.

Drawing information: Cockroach grid shows the layout of the second part of experiment, where a cockroach was let loose and then was recorded if it went to where narcotics were placed.

Bottom photo: Pavlick in the lab.

Categories:

College of Science and EngineeringGraduate SchoolResearchUniversity News