Idaho State University affiliate faculty member Woods trying to help solve mysteries of tiny pre-Aztecan beads made 1,200 years ago in Mexico

September 28, 2011

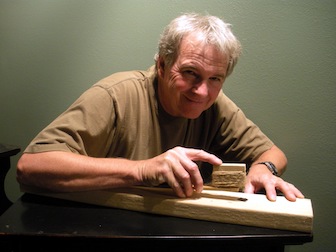

Idaho State University anthropologist and flintknapper Jim Woods of Twin Falls is trying to help solve the mysteries surrounding tiny beads produced from of a special type of obsidian in pre-Aztecan Mexico, about 1,200 years ago.

The beads are from 1/8- to ¼-inch in diameter and are made from a type of obsidian that has microscopic air pockets that refract light, giving the beads a gold shimmer when light is shined on them, similar to tiger’s-eye gemstones.

The beads were only discovered about 10 years ago at the Teotihuacan archaeological site near Mexico City, where the largest ancient pyramids in the New World are found. Teotihuacan was an ancient city to the Aztecs and was considered the birthplace to the gods by them.

The beads were only discovered about 10 years ago at the Teotihuacan archaeological site near Mexico City, where the largest ancient pyramids in the New World are found. Teotihuacan was an ancient city to the Aztecs and was considered the birthplace to the gods by them.

"The beads are made of a stone that looks like metal," Woods said. "They glow like pyrite, almost gold. It's really beautiful stuff and all of it was mined out of one giant quarry."

Woods, an affiliate Idaho State University anthropology faculty member and a professor of anthropology at the College of Southern Idaho, is working with a collaborator Alejandro Pastrana, from the Mexico National Institute of Anthropology and History in Mexico City, to replicate and better understand the significance of these beautiful beads.

"What I find interesting is that at first the beads seem like such simple, mundane things, but it has turned out to be quite a challenge for modern archeologists to replicate making them and to understand their significance," Woods said.

Pastrana contacted Woods for help studying the beads around a year ago, about the same time a workshop for making the beads was discovered at a Teotihuacan quarry where the obsidian for making the beads and famous Aztecan blades was mined. Woods is helping Pastrana understand how pre-Aztec craftsmen made the beads from thin fragments of obsidian blades.

Woods said he is now one step away from replicating making the beads. The ancient Mexican craftsmen were famous for making obsidian blades about 4 to 8 inches long that were ½-inch wide and 1/16th-inch thick.

Woods said he is now one step away from replicating making the beads. The ancient Mexican craftsmen were famous for making obsidian blades about 4 to 8 inches long that were ½-inch wide and 1/16th-inch thick.

"It was a very complex process to make these blades," he said, "But they would make notches about an inch apart on the blade, and then break a square piece about an inch in diameter to start making the bead."

The next step is the one Woods and colleagues are having trouble replicating. Once the craftsmen had the inch-square pieces they would use some type of tool to tap the center of the square piece to punch out a cone piece (think of seeing a cone in a windshield or piece of glass that has been dinged). They would then chip out the center of the piece, smoothing it, and then round the square outside edge into a circle.

"We can do everything but punch the hole out of the center of the square," he said. "When we try we usually break the square."

Woods has now developed a simple wooden device that he thinks will do the job on breaking out the center cone, but he hasn’t had time to try it out.

"We're getting closer. It appears so simple, but we haven’t quite unlocked it," he said.

Another thing Woods and his colleagues haven’t quite unlocked is the significance of the beads.

"At first, we thought the beads worn by everybody, but researchers are coming to the conclusion that the beads, were not worn as common jewelry, but were worn by warriors and ambassadors," Woods said. "They were sewn on clothing and worn as status symbols. They're beyond simple beads and Mexican researchers are calling them sequins, sort of equated with the brass buttons and pendants soldiers wear today."

Researchers have found as many as dozens of the beads in burials, but some drawings show white cotton garments adorned with up to a hundred beads.

Learning about the sequin-like beads was bolstered when researchers found the workshop where the beads were made. Pastrana was able to send Woods 20 beads and fragments of others, which are on temporary loan from the Mexico National Institute of Anthropology and History.

"They found lots and lots of pieces and we were able to lay them out in proper sequence so we could see how they were made," Woods said.

He said that modern technologies have greatly enhanced the ability for researchers from different countries, separated by a long distance, to collaborate on this type of research project.

"It's interesting how easy it has been to work back and forth between countries," Woods said. "Ten years ago, this wouldn't have been possible. It would have taken 10 years to accomplish what we have in the last year, and we've each only been working on this when we’ve had the spare time to do it."

Woods said he was able to use an electronic microscope that cost "a couple hundred dollars" that plugged into the USB port of his computer to take high-resolution photos of the diminutive beads. The researchers could then send pictures back and forth of their discoveries, and he also temporarily posted videos of his research discoveries and questions on YouTube for his colleagues in Mexico to see.

"It's intriguing how technology is allowing us to do things we haven't done before," Woods said.

###

Categories: